by Thomas Nelson Winter, from "Apology as Prosecution: The Trial of Apuleius" (Diss. Northwestern University, 1968), pp. 9–17.

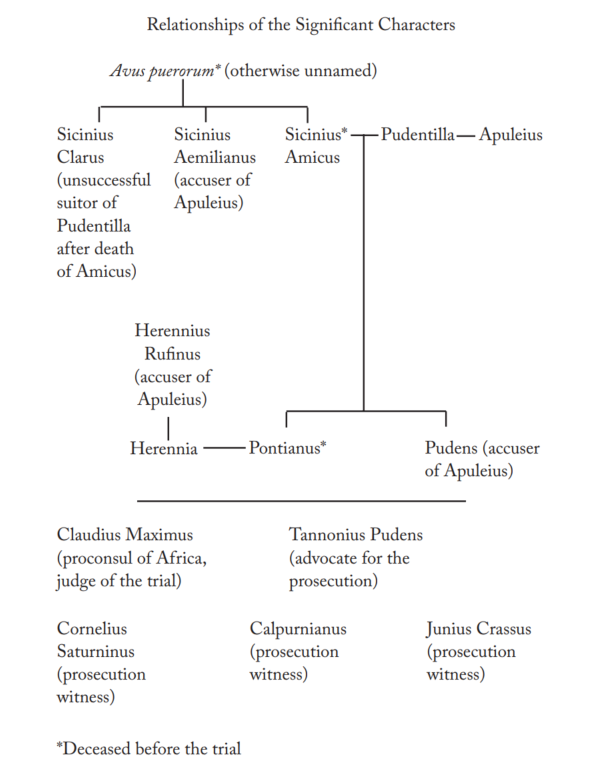

The series of events which culminated in the trial began some sixteen years before it, with the death of Sicinius Amicus. He left his two sons, Pontianus and Pudens, in the potestas of his father, but his widow, Pudentilla, supported them, and remained single to protect their interests (68.2–3) Her father-in-law opposed this policy. Apparently wishing to keep her property in the family, he wanted to have her marry another of his sons, Sicinius Clarus. He discouraged all other suitors, and threatened to disinherit her two sons if she should marry anyone else. Thus constrained, she agreed to have the marriage contract drawn up, but put off the marriage itself by various ruses. Thus, at her father-in-law’s demise, she was still single, but her sons duly inherited his property (68.6).

This left Pudentilla, now almost fourteen years a widow (68.2) and not yet forty (89), free to consider a second husband of her own choosing. Somehow Sicinius Aemilianus still hoped she would marry his brother Clarus. Aemilianus sent Pontianus a letter asking that he support the match. Unfortunately for his purpose, it is apparent that he had no means of dispatching a letter to Rome, for he was obliged to ask Pudentilla to have it sent (70. 4). It is a measure of her prudence that she never sent it, but sent Pontianus a letter of her own, mentioning her loneliness, and suggesting that Pontianus was himself at the age where he ought to marry. She also mentioned in this letter that the Sicinii brothers were still trying to have her marry Sicinius Clarus (70.2,5). Pontianus came straight home—his grandfather’s bequest had been somewhat slender, and his right to a share of his mother’s estate, valued at four million sesterces, was not yet attested, but rested on an unwritten agreement (71.5-7). It often happened that the wife’s property became entirely her husband’s, and an avaricious step-father, he feared, would seriously jeopardize his future (71.5).

This was the situation when Apuleius, exhausted by a journey toward Alexandria, was obliged to stop and recover in Oea. He stayed in bed several days in the home of his friends, the Appii, intending to resume his travels on recovery (72.1-2). Pontianus had other plans for him. He had known Apuleius when both were in Athens, and had decided that the Platonic philosopher would make a safe and suitable husband for his mother. Consequently, he called on Apuleius, convinced him that he should not leave soon, but should await the next winter before resuming his travels (winter seems to have been the most healthful time to traverse North Africa), and finally persuaded him to spend the interval at his mother’s house. Pontianus then pleaded with the Appii to turn their guest over to him (72.3-6).

Apuleius, recovered from his ailment, delivered a discourse “On the Majesty of Aesculapius” in the local basilica. The oration was enthusiastically received—the crowd shouted an invitation to stay in the town and become a citizen of Oea (73.2). Pontianus took the good will of the crowd as a divine and favoring omen, and broached his plan for Apuleius’s marriage to his mother. He told Apuleius that, of all those eligible, he was the only one whom he could trust to protect his interests (73.3). But Apuleius was still a bachelor at heart (72.5 and 73.5), and was not completely persuaded until a full year later (73.7). Even then, he and Pudentilla (who might have been won over at the start [73. 8]) decided to wait at least until Pontianus should marry and Pudens should don the toga virilis.

Pontianus made an unfortunate choice. His intended bride was the daughter of the infamous former actor, Herennius Rufinus. Although Rufinus’s father had bequeathed him three million sesterces (which he had preserved by putting the sum in his wife’s name when he declared bank ruptcy [75.5-8]), Rufinus was now a financial and moral bankrupt whose income was largely derived from his wife’s amorous adventures1 (75 passim).

But such an income could not continue forever:

Ceterum uxor iam propemodum vetula et effeta totam domum contumeliis [lacuna] abnuit. Filia autem per adulescentulos ditiores invitamento marris suae necquiquam circumlata, quibusdam etiam procis ad experiundum permissa, nisi in facilitatem Pontiani incidisset, fortasse an adhuc vidua ante quam nupta sedisset (76.1–2).

But Pontianus was captivated, and nothing Pudentilla or Apuleius could say would keep him from marrying this girl, even though he knew that her previous marital experience had ended with a repudium, and that she ostentatiously had herself carried about in an eight-man sedan chair. She was the sort who would arrive for the wedding with her lips artificially reddened and her cheeks covered with rouge, and who would, even upon such an occasion, cast alluring eyes on the young men and show too much of herself, as everyone witnessed (76.3-5). Such had been the lessons from her mother. Her dowry had been borrowed the day before the wedding (76.6).

Why this borrowed investment? Herennius, as greedy as he was needy, had been told by Chaldaean seers that her husband would die after a short period, and the question of inheritance they answered with some lie designed to please (97. 4). It follows,then, that the solution for his finan cial difficulties was to seduce as rich a young man as possible. Now that Pontianus had accepted the offered bait, Herennius “in his presumption was already devouring the whole four million of Pudentilla” (77. 1).

The marriage accomplished, Herennius’ problem became Apuleius. He railed at his new son-in-law for affiancing his mother to Apuleius, and pressured him to undo the coming match—otherwise he would take back his daughter (77.1-3). Pontianus was convinced, but his mission to Mother was anything but a success. She, instead of complying, complained of his being inconstant and willy-nilly. The request not to marry Apuleius turned her usually most placid nature to “immovable wrath.” Finally, she told him she knew perfectly well he was pleading Rufinus’s case, and that she would thus need all the more the assistance of a husband to combat “his desperate greed” (77.5-7).

Pudentilla’s answer precipitated the first charge of “magic” of which we have any record. Like the one which first aroused Apuleius’s indignation in Claudius Maximus’s courtroom, the first instance was public and unofficial. On hearing the bad news with which Pontianus returned, “that dealer in his own wife so swelled with wrath and burned with rage that he called that most pure and chaste woman, in the presence of her own son, things worthy of his own bedroom, and, in the presence of several persons—whom I will name if you like—shouted that she was a whore, and I, a magician and a poisoner, and with his own hand he would bring about my death” (78.1-2). (This threat, incidentally, coupled with the fact that Herennius was a mime, allows Apuleius to twit him as follows: “With whose hand? Philomela’s? Medea’s? Clytemnestra’s?” [78.4]).

Seeing to what extent her elder son, Pontianus, had been corrupted by Herennius’ bad influence, Pudentilla wished to remove him from it. She therefore withdrew to her country villa and wrote her son, telling him to join her there. But at the time of writing, she had no suspicion of the extent of her son’s lapse of filial piety: before joining his mother, Pontianus actually turned his mother’s letter over to Herennius, and allowed himself to be led weeping through the forum while Herennius, deceitfully omitting the parenthesized context, read from the letter:

( . . . now that our malicious detractors have won you over, suddenly) Apuleius is a magician; he has bewitched me and I love him too much. Come to me then, while I am still in my right mind (82.2, compare 83.1).

This declamation ended, he would display the poor boy to the crowd, claiming the while that the rest of the letter was worse yet: too shameful, in fact, for public view. He therefore hid the rest of the letter from view, but showed the deceitfully truncated sentence to anyone who wished to look (82.1-4). The defamation was convincing, and much of Oea conceived a violent animosity toward Apuleius. Herennius Rufinus did what he could to make it grow. He continued haranguing in the forum, frequently brandishing the letter and saying: “Apuleius is a magician! She says so herself who knows and suffers! What more do you want?” (82.6).

We might wonder how Pontianus could face his mother after this, but with all Oea believing that his mother was in the clutches of a magician, public opinion might have obliged him to obey her summons and come to her aid, whether he wanted to see her or not. At any rate, come he did, and the reception was hostile. News of his performance had preceded him, and Pudentilla warned him about Rufinus, severely scoring him for his public reading and willful misrepresentation of her letter (87.8). He stayed at his mother’s country estate about two months, in which time Apuleius and Pudentilla were married.

Unfortunately, Pontianus was not Pudentilla’s only problem, for Pudens, too, was experiencing a lapse of filial piety. While still living at home, he secretly sent a letter to Pontianus which abused his mother “nimis irreverenter, nimis contumeliose et turpiter” (84. 4).

Apuleius, realizing the source of all their problems, and apparently not cursed with a love of money himself, after some difficulty persuaded Pudentilla to convey to her sons all that was properly theirs. This sum was given in real estate at the sons’ own evaluation. She was further persuaded to give them the most fruitful fields, a grand house “richly ornate,” a great supply of wheat, barley, wine, olive oil and other fruits, four hundred servants, and several flocks. This was to allow them to rest assured about the patrimony received and to entertain good hopes for the rest (93.3-5) .

Sometime earlier, when Pontianus was still in parental favor, Apuleius had written to the proconsul, Lollianus Avitus a letter in which he commended the young orator, Pontianus, to his attention. Apuleius’ next letter was full of the news of Pontianus’s incredible misbehavior. On discovering this, Pontianus humbly sought Apuleius’s forgiveness and a second letter of recommendation. Apuleius provided both, and the repentant Pontianus set off for Carthage, the proconsular seat (94.1-5). Pontianus was not the only person to experience conversion. All Oea heard of the premature gift of the sons’ heritage, and transferred their animosity from Apuleius to Herennius (94.1).

The interview with the proconsul passed pleasantly: on reading Apuleius’s missive, he congratulated Pontianus for his eximia humanitate, since he had quickly corrected his error (94.6). The proconsul wrote Apuleius an answer and charged Pontianus with delivering it to Apuleius.

Pontianus, en route home, fell ill and died. His will left his property to his mother and to Pudens. As Apuleius names her first in describing the testament of Pontianus, she apparently received the greater share (97.7). This fact may help explain why Pudens, on the occasion of his brother’s funeral, attempted, with the assistance of a band of brigands, to forbid his mother entry to the house she had given him (100.6).

It is important to note that in neither will which Pontianus wrote did he make his wife an heir (97). Pontianus thus nullified the effect of Herennius’ machinations, and thereby obliged him to repeat them on Pudens. Further, Pontianus’ will—apparently the latter of the two—confirmed all that Apuleius had said of the Herennius family:

Quippe qui ei [Herennia] ad ignominiam lintea ascribi ducentorum fere denariorum iusserit, ut intellegeretur iratus aestimasse eam quam oblitus praeterisse (97. 6).

Isaac Casaubon interpreted this legacy as one intended to brand his wife a harlot, citing Isidore: “Amiculum est meretricum pallium linteum; his apud veteres matronae inadulterio deprehensae induebantur” (Origines 19. 25).

Pontianus’s death and testament sufficed to make Pudens a center of attention. The two legacy-hunters, Rufinus and Aemilianus, each having once failed to construct a channel through which to divert Pudentilla’s resources, set a snare for Pudens and combined their efforts. Herennius aimed his widowed daughter at Pudens, who, to further this project, was easily removed to live with his uncle Aemilianus:

At ille puellae meretricis blandimentis et lenonis patris illectamentis captus et possessus, exinde ut frater eius animam edidit, relicta matre ad patruum commigravit, quo facilius remotis nobis coepta perfi cerentur (98.1).

Apuleius points out that under this arrangement, should Pudens die intestate, his estate would go “by law but not by justice” to Aemilianus (98.2). The latter apparently wished to secure his position, for he showed a sudden fondness for the boy, and a real willingness to please: living at home, he was still without the toga; in his uncle’s charge he is granted it immediately. He went to teachers and kept good company when at home; he now goes to brothels, carouses with the worst sort, is allowed to act as lord of house and household, and goes to the gladiators’ school, where the keeper himself teaches him the names, battles, and wounds of the fighters (98.5-7).

Pudentilla, suffering from her son’s outrageous conduct toward her, became ill and disinherited Pudens. But Apuleius wished to pour coals of kindness on his head, and went to the extreme of threatening to leave her to get his way, so great was her distaste for her son. Pudens was not only reinstated, but made first heir (99.4). This was not made known to Aemilianus nor to his young ward until Apuleius announced it at the trial (99.5).

This, in sum, was the situation at the time of the trial: Apuleius had three enemies leagued against him, Herennius Rufinus, Aemilianus, and Pudens. Their leader Herennius would allow no opportunity for defaming Apuleius to pass unused, no matter how unfair or unjust it might be. This he demonstrated beyond any question on the occasion of his public readings. The trial took place three years after Apuleius’ arrival in Oea (55.10). The campaign of defamation, the reader will recall, had begun about two months before the wedding of Apuleius and Pudentilla, an event which took place somewhat more than a year after Apuleius’ arrival (73.7 and 9). By the time of the trial, then, Apuleius had been subjected to two years of hatred and slander.

[1] Apuleius’ unrestrained narration of Herennius’ major source of income has shocked modern critics into considering it exaggerated, or at least in bad taste. But since Roman law offered the remedies of iniuria to the husband of the insulted wife (Gaius 3.2.21), Apuleius must have known his statements would make him liable if he were not telling the truth. ↩