577. The use of the accusative and infinitive in indirect discourse (ōrātiō oblīqua) is a comparatively late form of speech, developed in the Latin and Greek only, and perhaps separately in each of them. It is wholly wanting in Sanskrit, but some forms like it have grown up in English and German.

The essential character of indirect discourse is, that the language of some other person than the writer or speaker is compressed into a kind of substantive clause, the verb of the main clause becoming Infinitive, while modifying clauses, as well as all hortatory forms of speech, take the subjunctive. The person of the verb necessarily conforms to the new relation of persons.

The construction of indirect discourse, however, is not limited to reports of the language of some person other than the speaker; it may be used to express what any one—whether the speaker or some one else—says, thinks, or perceives, whenever that which is said, thought, or perceived is capable of being expressed in the form of a complete sentence. For anything that can be said etc. can also be reported indirectly as well as directly.

The use of the infinitive in the main clause undoubtedly comes from its use as a case form to complete or modify the action expressed by the verb of saying and its object together. This object in time came to be regarded as, and in fact to all intents became, the subject of the infinitive. A transition state is found in Sanskrit, which, though it has no indirect discourse proper, yet allows an indirect predication after verbs of saying and the like by means of a predicative apposition, in such expressions as “The maids told the king [that] his daughter [was] bereft of her senses.”

The simple form of indirect statement with the accusative and infinitive was afterwards amplified by introducing dependent or modifying clauses; and in Latin it became a common construction, and could be used to report whole speeches etc., which in other languages would have the direct form. (Compare the style of reporting speeches in English, where only the person and tense are changed.)

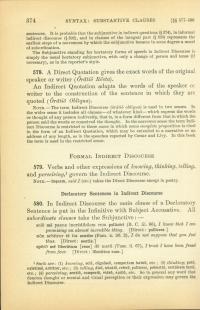

The subjunctive in the subordinate clauses of indirect discourse has no significance except to make more distinct the fact that these clauses are subordinate; consequently no direct connection has been traced between them and the uses of the mood in simple sentences. It is probable that the subjunctive in indirect questions (§ 574), in informal indirect discourse (§ 592), and in clauses of the integral part (§ 593) represents the earliest steps of a movement by which the subjunctive became in some degree a mood of subordination. The subjunctive standing for hortatory forms of speech in indirect discourse is simply the usual Hortatory Subjunctive, with only a change of person and tense (if necessary), as in the reporter's style.

578. A direct quotation gives the exact words of the original speaker or writer (Ōrātiō Rēcta). An indirect quotation adapts the words of the speaker or writer to the construction of the sentence in which they are quoted (Ōrātiō Oblīqua).

Note— The term indirect discourse (ōrātiō oblīqua) is used in two senses. In the wider sense it includes all clauses—of whatever kind—which express the words or thought of any person indirectly, that is, in a form different from that in which the person said the words or conceived the thought. In the narrower sense the term indirect discourse is restricted to those cases in which some complete proposition is cited in the form of an indirect quotation, which may be extended to a narrative or an address of any length, as in the speeches reported by Cæsar and Livy. In this book the term is used in the restricted sense.

579. Verbs and other expressions of knowing, thinking, telling, and perceiving,1 govern the indirect discourse.

Note— Inquam, (said I, etc.) takes the direct discourse except in poetry.