[1.pref.5] Ō quam contempta rēs est homō nisi suprā hūmāna surrēxerit! quamdiū cum adfectibus conluctāmur, quid magnificī facimus? etiamsī superiorēs sumus, portenta vincimus. quid est cūr suspiciāmus nōsmet ipsōs quia dissimilēs dēterrimīs sumus? nōn videō quārē sibi placeat quī rōbustior est in valētūdināriō: [1.pref.6] multum interest inter vīrēs et bonam valētūdinem. effūgistī vitia animī? nōn est tibi frōns ficta, nec in aliēnam voluntātem sermō compositus, nec cor involūtum, nec avāritia quae quidquid omnibus abstulit sibi ipsī neget, nec luxuria pecūniam turpiter perdēns quam turpius reparet, nec ambitiō quae tē ad dignitātem nisi per indigna nōn dūcet: nihil adhūc cōnsecūtus es: multa effūgistī, tē nōndum.

Virtūs enim ista quam adfectāmus magnifica est nōn quia per sē beātum est mālō caruisse, sed quia animum laxat et praeparat ad cognītiōnem caelestium, dignumque efficit quī in cōnsortium <cum> deō veniat. [1.pref.7] tunc cōnsummātum habet plēnumque bonum sortis hūmānae cum, calcātō omnī mālō, petît altum et in interiōrem nātūrae sinum vēnit. tunc iuvat inter ipsa sīdera vagantem dīvitum pavīmenta rīdēre et tōtam cum aurō suō terram, nōn illō tantum dīcō quod ēgessit et signandum monētae dedit, sed illō quod in occultō servat posterōrum avāritiae. [1.pref.8] nōn potest ante contemnere porticūs et lacūnāria ebore fulgentia et tonsilēs silvās et dērīvāta in domōs flūmina quam tōtum circuît mundum, et terrārum orbem supernē dēspiciēns angustum ac magnā ex parte opertum marī, etiam eā quā extat lātē squālidum et aut ustum aut rigentem, sibi ipse dīxit: ‘hoc est illud pūnctum quod inter tot gentēs ferrō et igne dīviditur!’

[1.pref.9] Ō quam rīdiculī sunt mortālium terminī! ultrā Histrum Dācus <nostrum> <arc>eat imperium, Haemō Thrācēs inclūdant, Parthīs obstet Euphrātēs, Dānuvius Sarmatica ac Rōmāna disterminet, Rhēnus Germāniae modum faciat, Pȳrēnaeus medium inter Galliās et Hispāniās iugum extollat, inter Aegyptum et Aethiōpās harēnārum inculta vastitās iaceat. [1.pref.10] sī quis formīcīs det intellēctum hominis, nōnne et illae ūnam āream in multās prōvinciās divident? cum tē in illa vērē magna sustuleris, quotiēns vidēbis exercitūs subrēctīs īre vēxillīs et, quasi magnum aliquid agātur, equitem modo extrēma cingentem, modo ulteriōra explōrantem, modo ā lateribus adfūsum, libēbit dīcere ‘it nigrum campīs agmen.’ formīcārum iste discursus est in angustō labōrantium. quid illīs et vōbīs interest nisi exiguī mensura corpusculī? [1.pref.11] pūnctum est istud in quō navigātis, in quō bellātis, in quō rēgna dispōnitis: minima etiam cum illīs utrimque ōceanus occurrit.

Sūrsum ingentia spatia sunt, in quōrum possessiōnem animus admittitur, <s>ed ita, sī sēcum minimum ex corpore tulit, sī sordidum omne dētersit et expedītus levisque ac sē contentus ēmicuit. [1.pref.12] cum illa tetigit, alitur, crēscit, velut vinculīs līberātus in orīginem redit, et hoc habet argūmentum dīvīnitātis suae quod illum dīvīna dēlectant, nec ut aliēnīs sed ut suīs interest. nam sēcūrē spectat occāsūs sīderum atque ortūs et tam dīversās concordantium viās; observat ubi quaeque stēlla prīmum terrīs lūmen ostendat, ubi columen eius [summum cursūs] sit, quousque dēscendat. cūriōsus spectātor excutit singula et quaerit. quidnī quaerat? scit illa ad sē pertinēre.

[1.pref.13] Tunc contemnit domiciliī priōris angustiās. quantum est enim quod ab ultimīs lītoribus Hispāniae usque ad Indōs iacet? paucissimōrum diērum spatium, sī nāvem suus ferat ventus. at illa regiō caelestis per trīgintā annōs vēlōcissimō sīderī viam praestat nusquam resistentī sed aequāliter cito. illīc dēmum discit quod diū quaesît, illīc incipit deum nōsse. quid est deus? mēns ūniversī. quid est deus? quod vidēs tōtum et quod nōn vidēs tōtum. sīc dēmum magnitūdō illī sua redditur, quā nihil maius cōgitārī potest, sī sōlus est omnia, sī opus suum et intrā et extrā tenet.

notes

Selection 10 (1 pref. 5–13): The ethical value of the study of natural science

Seneca argues that the study of the physical world allows us to better understand the cosmos as a whole and attain a “view from above.” In studying the larger universe we acquire the proper perspective on the human world and its troubles and, ultimately, become closer to God, who is that universe. We recognize that the human animus (the mind as the seat of consciousness) is a small portion of the divine inside of each of us, which delights in doing this sort of research. These ideas underlie and motivate the treatise as a whole. As Hadot (1995: 245) puts it, “The view from above thus leads us to consider the whole of human reality, in all its social, geographical, and emotional aspects, as an anonymous, swarming mass, and it teaches us to relocate human existence within the immeasurable dimensions of the cosmos. Everything that does not depend on us, which the Stoics called indifferent (indifferentia)—such as health, fame, wealth, and even death—is reduced to its true dimensions when considered from the point of view of the nature of the all.” Seneca encourages this perspective in some of his letters as well, such as Ep. 92.30–34.

Further Reading: Hadot 1995: 238–250; Inwood 2009.

[1.pr.5] Ethical struggle on the merely human plane, without natural science, is impoverished.

read more

This preface begins by mentioning the joy and satisfaction to be gained by studying the secrets of natura and approaching a larger understanding of God, fate, and human limitations. We possess an innate love of contemplating the natural world, and should do so. We can truly accomplish very little if we deal merely with human matters such as the passions.

O quam: introducing an exclamation (AG 269.c).

contempta: “trivial,” “negligible” > contemno.

surrexerit: future perfect > surgo in the protasis of a future more vivid condition (AG 516).

humana: “human affairs,” acc. n. pl. substantive

quamdiu cum adfectibus colluctamur: coping with damaging emotions is a central goal of Stoic ethics. In his ethical writings Seneca stresses the daily fight against such passions (adfectus), and a central theme of his tragedies the inability of characters to overcome their passions. See Konstan 2015 for a concise overview of Seneca’s perspective on the passions.

magnifici: partitive genitive (AG 346)

portenta vincimus: “we overcome only monsters,” no worthy goal or great achievement.

read more

For portentum in a moral sense, “a monster of depravity,” see LS portendo II.A. Seneca will employ forms of portentum to describe some of Hostius Quadra’s depraved actions at this Book’s conclusion (1.16.3, 1.16.5). In addition, this phrase recalls the preface of Book 3, where Seneca wrote that “the greatest victory is to have defeated one’s vices” (qua maior nulla victoria est, vitia domuisse, 3.pr.10). Now, such a victory is not nearly enough.

cur suspiciamus nosmet ipsos: indirect question (AG 574). The -met intensifier (AG 143.d) and ipsos stress the vanity of accolades we give to ourselves for making philosophical progress.

dissimiles deterrimis: “very different from the worst (people).” dissimilis takes the dative (AG 385). This sort of comparison shows how limited our perspective truly is.

quare sibi placeat: another indirect question (AG 574). placeat takes the dative (AG 367).

in valetudinario: according to Seneca we are all ethically “sick” in some way, and philosophy can help heal the mind just as doctors heal the body. See Ep. 27.1: “I am lying in the same hospital as you, and I am speaking to you about our shared illness and sharing remedies for it” (tamquam in eodem valetudinario iaceam, de communi tecum malo conloquor et remedia communico). In general, Roman hospitals were found in army camps and not in cities, where such care would take place in the home.

[1.pr.6] Ethical progress in itself is not enough; its purpose is to prepare the mind for the contemplation of the heavens and the divine.

read more

True virtue is more than simply living an ethical life. That might still be too solipsistic. The virtue that comes about by study of the natural world is truly magnifica, which clarifies Seneca’s statement in 1.pr.5: quid magnifici facimus?

multum interest: “there is a great difference.”

vires: “physical strength” (looking back to robustior in the previous sentence) rather than good health in general.

effugisti vitia animi: these vices are subsequently catalogued. Ring-composition with effugisti encloses this paragraph.

est tibi frons ficta: tibi is dative of possession (AG 373), and applies also to the string of nominatives that follows, sermo ... cor ... avarita ... luxuria ... ambitio.

read more

Dissimulation was rampant in Nero’s court, and various “yes-men” were able to win power and influence. Seneca himself had previously bowed to power politics (see his Consolatio ad Polybium) and hostile readers of Seneca believe much of his work betrays almost schizophrenic dissimulation (see Rudich 1997), whereas others may see theatricality behind almost all of the actors/actions (see Bartsch 1994). Ep. 80.7–11 discusses the idea that life is like the stage with pervasive role-playing.

in alienam voluntatem: “according to someone else’s will.” The dangers of flattery were also mentioned in the preface of Book 4a and are a central theme of Tacitus’ history of the period, the Annals.

involutum: “wrapped up,” “concealed”

avaritia: greed is that it is never satiated (Ep. 108.9: “many things are lacking in poverty, everything is lacking to greed,” desunt inopiae multa, avaritiae omnia). Avaritia comes up relatively often in NQ, especially as a force that inspires exploration, but for the wrong reasons (e.g. mining in Book 5, see Selection 6).

quae: fem. nom. sing., subject of neget in relative clause of characteristic (AG 535).

luxuria … reparet: the antecedent of quam is pecunia and it introduces a relative clause of characteristic. Note the rhetorical amplification from turpiter to turpius and the repetitive “p” and “t” sounds which give this sententia a memorable rhythm. As with greed, luxury is another vice that appears often in NQ (see Selections 5 and 12).

ambitio: originally denoted the act of canvassing for office, but gradually came to mean “a self-interested striving for success,” especially in politics. Earlier in the work, Seneca notes that Lucilius is “a stranger to ambition, a friend to leisure and literature” (scio quam sis ambitioni alienus, quam familiaris otio et litteris, NQ 4a.pr.1).

te ad dignitatem nisi per indigna: note the wordplay between dignitatem and indigna. dignitas means “rank,” “public office.” indigna would include the need to flatter the voters or powerful individuals to gain office.

multa effugisiti, te nondum: “you have escaped many (bad) things, (but) you have not yet escaped yourself” by gaining the loftier perspective of natural science.

Virtus … quam adfectamus magnifica est: virtus in the Stoic view is a moral excellence never fully achieved by ordinary mortals, hence adfectamus, “we strive for.” Note the wordplay with the previous paragraph, adfectibus ... adfectamus, and magnifici ... magnifica.

per se beatum est malo caruisse: the infinitive is the neuter subject of est (AG 452); careo takes an ablative of separation, malo (AG 401).

ad cognitionem caelestium: ad + accusative expressing purpose. cognitio takes an objective genitive (AG 347). Seneca draws on both meanings of caelestia: “heavenly objects,” and “divine things” (LS caelestis II.A.4).

dignum ... qui … veniat: dignus frequently introduces a relative clause of characteristic (LS dignus I.β). Translate “worthy to come.”

read more

The animus is a type of cosmic traveler that can escape the bounds of the body and the earth and come to know the divine. As Williams (2012: 3) states, “For Seneca, by studying nature we free the mind from the restrictions and involvements of this life, liberating it to observe, and luxuriate in, the undifferentiated cosmic wholeness that is so distant from the fragmentations and disruptions of our everyday existence.” For a similar conception elsewhere in Seneca, see Ep. 31.8 and 59.14.

[1.pr.7] The enlarged perspective of natural science allows us to despise human wealth and luxury.

read more

The movement of the soul to the heavens from which to gaze down on earth is also depicted in Cicero’s Dream of Scipio (Rep. 6.9–29). The mind is able to achieve this viewpoint during meditatio as well (cf. Ep. 102.21). It rejoices in this movement and ridicules costly buildings and gold.

tunc … cum: correlatives, “then… when… ” (AG 323.g).

habet: supply animus as the subject from the previous sentence.

calcato omni malo: ablative absolute, building on the previous section’s idea of malo caruisse.

petît: perfect tense (= petivit, AG 181), as is vēnit at the end of the sentence.

altum: “the lofty and the deep” (Corcoran). altus can have both meanings. Seneca likes to play with such vertical highs and lows in this work. See Trinacty 2018.

in interiorem naturae sinum: “into the inmost secrets of nature” (LS sinus II.2.d). There is some personification of natura here. For a similar idea, see NQ 7.30.6 in Selection 9 and 1.pr.3.

iuvat: “it is pleasing,” impersonal verb with the accusative vagantem [animum] (AG 388.c) and the infinitive ridere.

pavimenta: marble inlaid floors favored by the rich, like the one from Pompeii at the House of the Faun.

ridere: rather than feeling envy or greed, the exalted mind laughs at displays of wealth (elaborate floors) as well as all the gold on earth (cf. NQ 5.18.16 for similar laughter). In his treatise de Ira, Seneca advises us to “withdraw far away and laugh” (recede longius et ride! 5.37.3) when we are growing angry at the behavior of those around us.

non illo tantum … sed illo: “not only do I speak about the gold… but also the gold… ”

quod egessit: “that (gold) which it (the earth) has produced,” i.e., what has already been mined.

signandum monetae: “to be struck for money.” Supply aurum with signandum. The mint in Rome was connected to the temple of Juno Moneta; as a common noun, moneta can refer by extension to any mint, or be used as a synonym for pecunia or nummus.

in occulto: = “in hiding,” “in a hidden place,” an important idea for the work as a whole, as Seneca often gives reasons for hidden phenomena. At the opening of the work, he stated his task would be to discover occulta (3.pr.1) and at the close of the work he will say it is through such investigation of occulta naturae (2.59.2) that our souls are strengthened (see Selection 14).

posterorum: “of later generations.” See the digression about mining in Book 5 (Selection 6).

[1.pr.8] It is not possible to despise worldly goods until one attains this “view from above.”

read more

Inwood writes that in this section, “Seneca then expatiates eloquently on how it is that the study of cosmology carries man beyond his own parochial interests—and parochial they are, since the earth on which we live is so small compared to the size of the universe as a whole” (2005: 191).

non potest ... circuit ... sibi ipse dixit: animus is the subject of this long sentence, supplied from above.

ante… quam: “until,” with totum circuit mundum (AG 434). The long wait for the quam gives the feeling that Seneca could continue to catalogue the trappings of the rich indefinitely.

porticus: accusative plural. There were numerous public colonnades in the city of Rome, and they were found at private villas as well (such as Villa Poppaea at Oplontis).

lacunaria ebore fulgentia: “recessed panelled ceilings gleaming with ivory,” emblematic of conspicuous consumption by the rich (see Horace, Odes 2.18.1–2; Seneca, Ep. 114.9 and 115.9). A French manuscript of the NQ shows Seneca at work on the text in a room with a paneled ceiling!

tonsiles silvas: manicured gardens are attested in Rome from the 1st century BCE (e.g. the elegant Horti Lucullani) and one can find reconstructed pleasure gardens in some of the houses in Pompeii, as well as the Roman style Getty Villa in Malibu.

derivata … flumina: water features were common in luxury villas, especially fish ponds and swimming pools; but water could also be used in plumbing (cf. Ep. 100.6) or baths (Ep. 86.7). Diverting streams was not uncommon, to provide water for villa crops (especially vines) and meadows (Marzano 2007: 93–4). Seneca describes the Villa Vatia having a canal cut between the sea and an inland lake to supply fish when there are storms at sea (Ep. 55.6). Seneca lambasts such luxury and the “foodie” desire for red mullet in NQ 3.17.1–18.7.

totum circuît mundum: circuît = circumivit, pf. > circumeo. animus is still the subject. This tour of the universe is the culmination of Seneca’s original desire to “traverse the world” (mundum circumire, 3.pr.1).

terrarum orbem: orbis terrarum is the standard way to refer to the world in Latin.

angustum: from on high the whole world seems small and insignificant.

magna ex parte opertum mari: mari is ablative of means (AG 409); magna ex parte = “for the most part.”

ea qua extat: the antecedent is pars. The idea that terra firma “stands out” from the sea emphasizes the vast expanse of water that covers the world.

squalidum: “uncultivated” wasteland

ustum: “scorched” by the sun, > uro

rigentem: “frozen” (LS rigeo III.1)

punctum: “pinpoint.”

read more

A similar point is made by Cicero in The Dream of Scipio (Rep. 6.16): “The spheres of the stars easily defeated the size of the earth, while the Earth itself seemed so tiny to me, that I was ashamed that our empire was little more than a pinpoint (punctum) on it.” For the exalted animus in Seneca, the very idea of worldy empire seems absurd. In another treatise he says, “This earth, with its cities and races and rivers and surrounding sea is reckoned as a pinpoint (puncti loco ponimus) when compared to the universe” (Cons. Marc. 6.21.2).

[1.pr.9] From the perspective of the universe, the contested boundaries between nations are ridiculously small.

read more

Seneca delineates the expanse of the Roman empire at this time—would Seneca’s questioning of how impressive it is rub Nero the wrong way? While the geographical features act as natural boundaries and are significant in size, from the cosmic point of view these are actually miniscule. Seneca says in Ep. 91.17: “Alexander the Great had begun to study geometry—a study that would make him wretched, when he learned how puny the earth is and how little of it he had captured. I say it again: he was wretched, for he should have realized that his title was unjustified: who can be ‘great’ in an area that is miniscule?” (trans. Graver and Long).

O quam: introducing an exclamatory sentence, as in 1.pr.5.

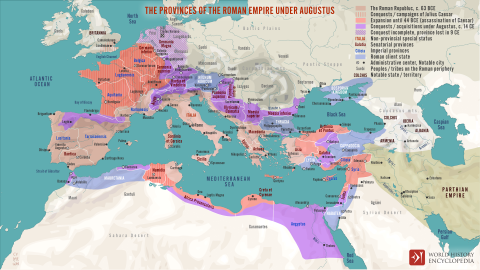

Histrum: Hister or Ister was the Roman name for the lower Danube , long the border between the Roman Empire and Dacia, what is now Romania. Dacia was largely independent of Roman influence until conquered by Trajan in AD 106, which is famously portrayed on his column. See map.

Dacos: “the Dacians” (the masculine nominative singular standing for the people as a whole).

read more

Under Nero, the legate Tiberius Plautius Silvanus brought more than 100,000 settlers from the region beyond the Danube to Moesia and reinforced Roman influence in the Scythian territories (Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 986), so despite what Seneca says quite a few Dacians did cross the Danube.

<nostrum> <arc>eat imperium: reading Oltramare's emendations. This makes more sense with the actual geopolitical situation at this time, which Seneca surely understood.

Haemo Thraces includat: “let the Thracians fence in the (Roman) empire with the Haemus,” i.e. the Balkan mountain range. In the Neronian period the Haemus range was the boundary between newly established provinces of Thracia (to the south) and Moesia Inferior (to the north). See map.

Parthis: the Parthians, based in what is now Iran, were Rome’s main imperial rivals in this period. The Euphrates River represented the notional boundary between Roman and Parthian spheres of control.

Sarmatica: the Sarmatians were a confederation of Iranian nomadic tribes who consolidated their power in the northern Black Sea steppe in the 4th to 2nd centuries BCE. In the 1st century BCE, they were allies of the Pontic king Mithradates VI during his war with Rome. Thereafter, the northern Pontic littoral was called Sarmatia, and the group was often mentioned by Latin writers. Seneca imagines their territory as bounded on the west by the Danube.

Aethiopas: “the Aethiopians” (acc. pl.). Seneca probably refers to the peoples of Upper Nubia around the kingdom of Meroe, south of Egypt and separated from it by the Nubian desert. Ancient Greek geographers, however, distinguished between “Aethiopia under Egypt” (i.e., Upper Nubia) and “Inner Aethiopia,” which seems to refer to sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, and this could be the reference here as well. See Ptolemy, Geography 4.7 (Aethiopia under Egypt) and 4.8 (Inner Aethiopia).

[1.pr.10] If ants had human minds they would go to war over tiny spaces, as we do.

si quis: introduces a mixed condition with a future less vivid protasis and a future more vivid apodosis (AG 516); quis for aliquis (AG 310.a).

nonne: expects an affirmative answer (AG 332.b).

illae: the ants

aream: could be any open space, but Seneca perhaps imagines a threshing floor used to separate grain (LS area II.c). It was usually circular, and hence it approximates an ancient conception of the earth.

divident: echoing the dividitur that ends 1.pr.8.

cum … sustuleris: cum temporal clause (AG 547). Although in previous sections it was the animus that was traveling into the celestial sphere, now Seneca imagines “you” (Lucilius or the reader) attaining such a viewpoint.

in illa vere magna: vere acts as a corrective to what had seemed “great” from an earthly point of view (see the following, quasi magnum aliquid agatur). As Gunderson (2015: 68) puts it, “The philosophy of perspective provides one of the opening themes of the text as a whole. There we are told that we generally mis-measure phenomena because we look at them from our own meager standpoint.”

quotiens videbis exercitus … ire: videbis sets up indirect speech with exercitus the accusative subject of ire (AG 580). This image recalls the opening of Lucretius, De Rerum Natura Book 2 where one observes the movements of armies from far off (2.5–6, 40–46).

quasi magnum aliquid agatur: quasi introduces a conditional clause with the subjunctive (AG 524). Military action and imperialism more generally are cut down to size, a theme also highlighted earlier in the work in the preface to Book 3 (3.pr.5–6, 9–10).

modo… modo… modo… : “now… now… now… ” (AG 323.f). The movements of the cavalry, even with superlatives (extrema) and comparatives (ulteriora), are made minuscule by this view from above.

a lateribus adfusum: “massed at the flanks” of the main column, a military expression, see LS ab II.B.3 and OLD affundo 6.

‘it nigrum campis agmen’: a quotation of Vergil, Aeneid 4.404, in which Vergil compares the movement of Aeneas’ men to ants storing grain for the winter. Vergil himself plays with the reader’s perspective. What was a comparison for the reader soon becomes the point of view Dido (4.408), who is seeing this from her “high citadel” (arce ex summa). Her reaction is not the serene philosophical contemplation of the divine that Seneca encourages here.

formicarum: heavily empahsized by its position.

in angusto: not only emphasizing the tiny nature of their work, but also another recollection of the passage of the Aeneid, where the ants were carrying their food “on a narrow path” (calle angusto, Aen. 4.405). Note how this adjective is repeated from 1.pr.8 and will be found again at 1.pr.13. Seneca is artfully stressing this word and will conclude this preface with the observation, “I will know everything is tiny, having measured god” (sciam omnia angusta esse mensus deum, 1.pr.17).

quid illis et vobis interest: “what difference is there between those ants and you” (LS intersum II.B).

corpusculi: the small size of the body is emphasized with the diminutive.

read more

This word is repeated elsewhere when Seneca wants to underscore the insignificance of mankind or one’s life (e.g. NQ 6.2.3 and 6.32.8). When speaking about imperialist tendencies at 3.pr.10, Seneca writes, “We believe such matters are great because we are tiny: many things seem great, not from their true nature, but from our small stature.”

[1.pr.11] Our world is tiny, but the mind, if purified, has access to the vast world above.

read more

The mind can enter these regions on its own, provided it has transcended bodily concerns. This sort of ascent then can be achieved only by those who have made ethical progress. It is important that this is the mind (animus) and not the incorporeal soul (anima) making this journey; it is not to be envisioned as something that can only happen after death or in a dream, but it is part of one’s living activity and helps to stress how reason (ratio) should guide our lives.

punctum: the repetition stresses the point first made at the end of section 1.pr.8.

minima: “tiny,” further describing the regna.

etiam cum illis utrimque oceanus occurrit: “even when the Ocean runs to meet them on both sides,” i.e., the kingdom could take up the entire landmass of Europe, Africa, and Asia, but it would still be tiny from the cosmic viewpoint. occurro takes the dative, illis (AG 370).

animus: this sort of movement of the mind can happen with Stoic meditation and study.

read more

Meditation was part of the practice of Stoicism and the art of living that they endorsed. Meditations included imagining future troubles (praemeditatio malorum), reading and interpreting seminal texts, and practicing the self-mastering of the passions. Foucault (2001: 277) clarifies how this imaginative ascent helps us ethically: “we see how few things matter and endure. Reaching this point enables us to dismiss and exclude all the false values and all the false dealings in which we are caught up, to gauge what we really are on the earth, and to take the measure of our existence—of this existence that is just a point in space and time—and of our smallness.”

<s>ed ita: “but under these circumstances,” helping to explain the way the mind can be admitted to the world summit.

secum: = cum se.

minimum ex corpore: “very little of the body”

si sordidum omne detersit: the mind must be cleansed from earthly matters to make this ascent.

read more

This restates one of the reasons to study nature, according to Seneca at 3.pr.18: “First, we are removed from sordid things” (primo discedemus a sordidis). Like its English cognate, sordidus combines a physical meaning (“grimy, filthy”) and a moral one (“dishonorable, degrading, base,” and especially “miserly”). In Ep. 39.2 Seneca notes that “low and sordid things (sordida) delight no man of enlightened talent: the very sight of greatness calls to him and raises him up.”

se contentus emicuit: in Epistle 9, Seneca stresses that the ideal Stoic is self-sufficient (se contentus), repeating the phrase six times in the course of the letter. Fittingly for its travel into the firmament, such a mind “shines out” like a star (see emicuit at NQ 7.1.4).

[1.pr.12] The fact that the human mind delights in the study of natural science shows its kinship with the divine.

read more

The mind is a small piece of the divine and therefore when it is in the realm of the divine, it feels kinship and rejoices to be in its rightful place. As he will write: “the mind is the better part of us, in god there is nothing other than mind. God is complete reason” (1.pr.14). The mind must leave the body, which is a type of prison for it. See Ep. 65.16: “For this body is the weight and penalty of the mind: while thus oppressed, it is in chains, unless philosophy comes to its aid, bidding it gaze upon the world’s nature and so draw breath, releasing it from earthly things to things divine” (trans. Graver and Long). There is affinity as well as a delight in questioning—this is the model for the reader as well, who should be actively questioning the natural world and exercising ratio (see Ep. 95.10). Gauly 2014 offers a good overview of Seneca’s Stoic cosmology, and see Wright 1995 for cosmology in general.

cum illa tetigit: cum temporal clause (AG 545); illa (acc. pl. neut.) refers to the ingentia spatia of the celestial sphere.

vinculis liberatus: vinculis is ablative of separation (AG 401). The metaphor reflects the ubiquity of slavery in the Roman world and the Platonic conception of the soul being imprisoned by the body (see Apuleius, De Platone 2.20: “the soul of the wise man, when freed from its bodily bonds, returns to gods,” vinculis liberata corporeis, sapientis anima remigrat ad deos).

quod: “the fact that” (AG 572), further elaborating the argument of the mind’s divine nature.

nec ut alienis sed ut suis interest: interest takes the dative; the animus “takes part in” or “attends to” divine matters not because they are different, but because they are cut from the same cloth; see also Ep. 41 and Ep. 102.23–29.

secure: “without anxiety.”

read more

securitas is an ethical goal for Seneca (cf. Ep. 101.8–10). For Epicureans, knowledge of the natural world would help to achieve ataraxia (“lack of worry”). Knowing the causes of earthquakes or eclipses lessens the fear of them (see Epicurus’ Letter to Pythocles 85). For the Stoics, such knowledge also acts as a way to commune with the divine and spurs one to transcend the material world. Seneca also stresses how knowledge will help to conquer fear (esp. at the conclusion of Book 2, see Selection 14; and in Book 6, see Selection 7 and 6.32.4).

occasus ... ortus: accusative plural.

read more

Seneca believes mankind was endowed with a body made for such contemplation and thus, that one should do this because it follows nature. He writes in De Otio (5.4), “Nature caused man to stand upright to equip him for contemplation, so that he could examine the stars moving from their rising to their fall (ab ortu sidera in occasum labentia) and could bend his gaze as the stars turn.”

diversas concordantium vias: vias in the sense of “orbits” of stars. Although the orbits may differ, there is still harmony in the heavens.

ubi … ostendat: the first of three indirect questions (AG 586).

columen: “point of culmination,” the apex of its course.

[summum cursus]: “the highest altitude of its course.” There words are probably a marginal gloss on columen that has intruded upon the text.

quousque descendat: the Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians, and Greeks all used the heliacal risings of various stars for the timing of agricultural activities. The risings and fallings of stars and constellations are discussed in many surviving ancient works, such as Hesiod’s Works and Days, Aratus’ Phaenomena, and Manilius’ Astronomica.

curiosus spectator: “an engaged spectator.” The animus wants to know astronomical details because they directly pertain to it.

read more

Gunderson (2015: 69): “Natural questions are self-interested questions for the soul. Carefree on the one hand, the soul does nevertheless have a curiosity born of a care-for-the-self: though divergent, securus and curiosus are yoked terms. Apathetic spectatorship is replaced by engaged reflection. And this reflection takes the form of a collection of quaestiones that address themselves to various elements of nature.”

[1.pr.13] From this sublime point of view, one realizes not only how small the earth is, but also how to conceive of the true nature of God.

domicilii: the “home” encompasses the animus’ body, dwelling, and country.

quantum: can mean “how great” or “how small.” At first glance, the reader might assume that it is actually a great distance between India and Spain, but Seneca remarks that it is not that far.

paucissimorum dierum spatium: Seneca exaggerates for rhetorical effect. The fastest travel by open sea from Gades in Spain to Pelusium in Egypt would take approximately 32 days. After a land leg from the coast of Egypt to the Red Sea, the voyage to India would probably take another month. It has been hypothesized that Christopher Columbus thought Seneca was speaking about a westward journey and that this passage influenced his decision to sail to the New World (see Clay 1992).

suus: “favorable”; cf. Ep. 71.3: “if one does not know which harbor to approach, there can be no favorable wind (suus ventus).”

per triginta annos: per + time = “during, over a period of.” This refers to the orbit of Saturn and shows the vast expanse of the celestial realm, compared to the earthly travel from Spain to India.

nusquam resistenti sed aequaliter cito: “which never stops and maintains a constant velocity,” further defining the “very fast star” (velocissimo sideri).

quod diu quaesît: “that which it has long sought.” quaesît = quaesivit. animus is the subject.

nosse: = novisse.

mens universi: this idea may originate with the Presocratic philosopher Thales. Aëtius (a later compiler) explains, “Thales says that God is the mind of the world, and the totality is at once animate and full of deities” (Graham 2010: 35). Cicero also expresses this idea in De Natura Deorum (1.39).

non vides totum: hence the sort of exploration of the hidden and inner workings of nature that Seneca does in NQ. God is natura and therefore the study of natura is also the study of God.

magnitudo illi sua redditur: “his own greatness is rendered to him.” That is, God is given credit for his true magnificence only if we conceive of him as the totality of the universe.

qua nihil maius: qua is ablative of comparison (AG 406). The antecedent is magnitudo.

opus suum et intra et extra tenet: “he maintains his own work both from within and without.” God’s work is the universe and all that is in it.

vocabulary

quamdiū or quam diū: as long as

affectus –ūs m.: emotion, feeling

conluctor –ārī –ātus sum: to wrestle with

magnificus –a –um: splendid, magnificent

etiamsī: even if, although

superior superius: higher, superior, greater

portentum –ī: portent, omen, prodigy, monster

suspiciō suspicere suspexī suspectus: to take up; recognize; accept

dissimilis dissimile: dissimilar

dēterior dēterior dēterius; dēterior –ius; dēterrimus –a –um: worse

rōbustus –a –um: strong

valētūdinārium –iī n.: hospital

multum: much, a lot 1.pref.6

valētūdō valētūdinis f.: good health

effugiō effugere effūgī: flee from, escape the notice of, escape

frōns frontis f.: face, forehead

fīctus –a –um: false, insincere

involūtus –a –um: concealed, complicated

avāritia avāritiae f.: greed

luxuria luxuriae f.: luxury

reparō reparāre –āvī –ātum: recover, restore

ambitiō ambitiōnis f.: ambition, popularity, flattery

indīgnus –a –um: unworthy, shameful

effugiō effugere effūgī: flee from, escape the notice of, escape

adfectō adfectāre adfectāvī adfectātus: strive after, aim at, grasp

magnificus –a –um: splendid, magnificent

malum malī n.: evil, calamity

laxō laxāre laxāvī laxātus: relax, widen, undo

praeparō –parāre –parāvī –parātus: get ready, prepare (for)

cognitiō –ōnis f. : learning, knowledge of (+gen.)

cōnsortium –ī n.: partnership, community

calcō calcāre calcāvī calcātus: trample, trample on, spurn

malum malī n.: evil, calamity

interior –ius: inner, secret, deeper

vagor (1) –ārī or vagō vagāre vagāvī: wander, move

pavīmentum –ī n.: pavement, floor

dicō dicāre dicāvī dicātus: to devote

ēgerō ēgerere ēgessī ēgestum: carry out, pour forth

signō signāre signāvī signātus: to mark, stamp, coin

monēta –ae f. : mint, coin, money

dēdō dēdere dēdidī dēditus: to give up, surrender

occultus –a –um: hidden, concealed, secret

avāritia avāritiae f.: greed

porticus porticus f.: portico, colonnade.

lacūnar –āris n: paneled ceiling

ebur –oris n.: ivory

fulgeō fulgēre fulsī: gleam, flash, blaze

tonsilis tonsile: clipped, trimmed

dērīvō –āre: divert, draw off

circumeo (circueō ) –īre –iī/–īvī circuitus: to travel around, inspect

supernē: above, from above

dēspiciō –ere –spēxī –spectum: look down, look down on

angustus –a –um: narrow, close, constrained

operiō operīre operuī opertum: to cover, hide

ex(s)tō ex(s)tāre ex(s)tāvī ex(s)tātus: stand out, protrude, be visible

squālidus –a –um: squalid, wild, uncultivated

ūrō ūrere ussī ustum: to burn, scorch

rigeō –ēre: freeze, grow stiff

punctum –ī n.: point, spot, moment

rīdiculus –a –um: silly, ridiculous, funny 1.pref.9

terminus –ī m.: boundary, limit

Hister –trī m.: the Lower Danube River

Dācus (Dācicus) –a –um: Dacian

Haemus –ī m.: a mountain range in Thrace (the Balkan Mountains)

Thrāx –ācis or Thraex –aecis: of or from Thrace; Thracian

inclūdō inclūdere inclūsī inclūsus: shut in, confine, include

Parthus –a –um: Parthian

obstō obstāre obstitī obstātum: stand in the way, to constitute a boundary to

Euphrātēs –is m.: Euphrates river

Dānuvius –iī m.: the Danube river

Sarmaticus –a –um: Sarmatian (a confederation of Iranian nomadic tribes who ranged from the mouth of the Danube to the Caspian Sea)

Rōmānus –a –um: Roman

disterminō –āre: to serve as a boundary between, divide

Rhēnus –ī m.: the Rhine River (which divided Gaul and Germany)

Germānia –ae f.: Germany

Pȳrēnaeus –a –um: the Pyrenees Mountains

Gallia Galliae f.: Gaul; (pl.) the Gallic provinces

Hispānia –ae f.: Spain

extollō –ere: lift, raise up

Aegyptus) –ī f.: Egypt

Aethiops –opis m.: Ethiopian, from Ethiopia, including the peoples of Upper Nubia around the kingdom of Meroe, south of Egypt and separated from it by the Nubian desert

arēna (harēna) –ae f.: sand.

incultus –a –um: uncared for, neglected, unshorn

vāstitās –ātis f.: wasteland, desert, vastness

quis quid (after sī nisī ne or num): anyone/thing, someone/thing

formīca –ae f.: ant 1.pref.10

intellectus –ūs m.: intelligence, understanding

nōnne: introduces a direct question expecting the answer "yes"

area areae f.: threshing floor

subrigō subērigō –ere –rēxī –ērēctum: to raise up, lift up, erect

vexillum –ī n.: flag, standard, banner

explōrō explōrāre explōrāvī explōrātus: to explore, investigate

affundō affundere affūdī affūsum: dispatch to, send, mass

formīca –ae f.: ant

discursus –ūs m.: running up and down, running about

angustus –a –um: narrow, close, constrained

exiguus –a –um: small, puny, paltry

mēnsūra –ae f. : size, measure

corpusculum –ī n.: puny body.

punctum –ī n.: point, spot, moment 1.pref.11

nāvigō nāvigāre nāvigāvī nāvigātus: sail, put to sea

bellō bellāre bellāvī bellātus: wage war

dispōnō dispōnere dispōsuī dispōsitus: distribute, arrange, assign

minimus –a –um: very insignificant, smallest, very tiny

utrimque: from/on both sides

oceanus –ī m.: ocean

sūrsum or sūsum or sūrsus: upwards, high up, up above

possessiō possessiōnis f.: possession, occupation, property

admittō admittere admīsī admīssus: to send to, admit

minimus –a –um: very insignificant, smallest, very tiny

sordidus –a –um: dirty, filthy, shabby

dētergeō –ēre or dētergō –ere –tersī –tersum: wipe off, wipe clean

expedītus –a –um: unencumbered, unhampered

contendō contendere contendī contentus: to strain, exert

ēmicō ēmicāre ēmicuī ēmicātus: flash out, dart out, shoot out

līberō līberāre līberāvī līberātus: to free 1.pref.12

orīgō –inis f.: origin, source, birth

argūmentum –ī n.: proof, evidence, argument

dīvīnitās –tātis f.: divinity, nature of god, divination

dīvīnus –a –um: divine

dēlectō dēlectāre dēlectāvī dēlectātus: delight, please, fascinate

occāsus –ūs m.: setting (of stars)

ortus ortūs m.: rising (of stars)

dīvertō –ere –vertī –versus: to turn one’s self

concordō concordāre –āvī –ātum: harmonize, be in harmony/agreement

observō observāre observāvī observātus: to watch, observe

columen –inis n.: height, peak, zenith, summit

quoūsque or quō ūsque: until what time? until when? how long?

cūriōsus –a –um: careful, diligent

spectātor –ōris m.: beholder

excutiō excutere excussī excussum: to shake out, to examine, to investigate

domicilium –iī n.: home, dwelling 1.pref.13

angustiae –ārum f.: difficulty, tight spot, distress

Hispānia –ae f.: Spain

Indus –a –um: Indian, inhabitant of India

trīgintā; trīcēsimus or trīcēnsimus –a –um: 30th

vēlōx –ōcis: fast

nusquam: nowhere

resistō resistere restitī: resist, oppose, pause

aequāliter: equally, uniformly, in the same manner

cito citius (comp.) citissime (superl.): quickly

illic: in that place, there

dēmum: finally, at last

quaerō quaerere quaesīvī or quaes(i)ī: to seek

illic: there, in that place

ūniversus –a –um: all together, whole, entire

dēmum: finally, at last

maior māius: bigger

extrā: outside, beyond