[3.15.1] Quaedam ex istīs sunt quibus adsentīre possumus, sed hoc amplius cēnseō: placet nātūrā rēgī terram, et quidem ad nostrōrum corporum exemplar, in quibus et vēnae sunt et artēriae, illae sanguinis, hae spīritūs receptācula. In terrā quoque sunt alia itinera per quae aqua, alia per quae spīritus currit; adeōque ad similitūdinem illa hūmānōrum corporum nātūra fōrmāvit ut maiōrēs quoque nostrī aquārum appellāverint vēnās. [3.15.2] sed quemadmodum in nōbīs nōn tantum sanguis est sed multa genera ūmōris, alia necessāriī alia corruptī ac paulō pinguiōris (in capite cerebrum, mūcī salīvaeque et lacrimae, in ossibus medullae, et quiddam additum articulīs per quod citius flectantur ex lūbricō), sīc in terrā quoque sunt ūmōris genera complūra: [3.15.3] quaedam quae mātūra dūrentur (hinc est omnis metallōrum frūctus, ex quibus petit aurum argentumque avāritia, et quae in lapidem ex liquōre vertuntur); in quaedam vērō terra ūmorque putrēscunt (sīcut bitūmen et cētera huic similia). haec est causa aquārum secundum lēgem nātūrae voluntātemque nāscentium.

[3.15.4] Cēterum ut in nostrīs corporibus ita in illā saepe ūmōrēs vitia concipiunt: aut ictus aut quassātiō aliqua aut locī senium aut frīgus aut aestus corrūpēre nātūram; et suppūrātiō contrāxit ūmōrem, quī modo diuturnus est, modo brevis. [3.15.5] ergō ut in corporibus nostrīs sanguis, cum percussa vēna est, tam diū mānat dōnec omnis efflūxit aut dōnec <coeunte> vēnae scissūrā subsēdit atque interclus<us> est, vel aliqua alia causa retrō dēdit sanguinem, ita in terrā solūtīs ac patefactīs vēnīs rīvus aut flūmen effunditur. [3.15.6] interest quanta aperta sit vēna, quae modo consūmptā aquā dēficit, modo excaecātur aliquō impedimentō, modo coit velut in cicātrīcem comprimitque quam perfēcerat viam; modo illa vīs terrae, quam esse mūtābilem dīximus, dēsinit posse alimenta in ūmōrem convertere. [3.15.7] aliquandō autem exhausta replentur, modo per sē vīribus recollēctīs, modo aliunde trānslātīs. saepe enim inānia adposita plēnīs ūmōrem in sē āvocāvērunt; saepe terra, sī facilis in tābem est, ipsa solvitur et umēscit; īdem ēvenit sub terrā quod in nūbibus, ut spissētur <āēr>, graviorque quam ut manēre in nātūrā suā possit gignat ūmōrem; saepe colligitur rōris modō tenuis et dispersus liquor, quī ex multīs in ūnum locīs cōnfluit (sūdōrem aquilegēs vocant, quia guttae quaedam vel pressūrā locī ēlīduntur vel aestū ēvocantur). [3.15.8] haec tenuis unda vix fontī sufficit. at ex magnīs cavernīs magnīsque conceptibus excidunt amnēs, nōnnumquam leviter ēmissī, sī aqua tantum pondere sē suō dētulit, nōnnumquam vehementer et cum sonō, sī illam spīritus intermixtus ēiēcit.

notes

Selection 2 (3.15.1–8): Underground veins and arteries; the world/body analogy.

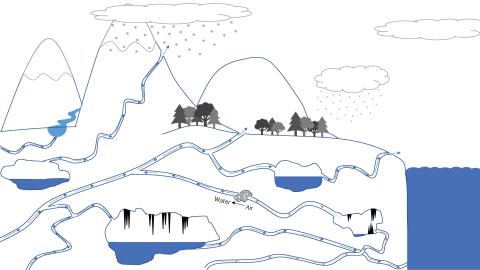

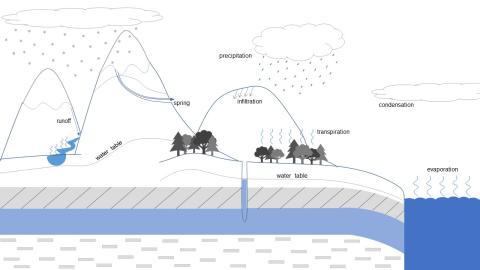

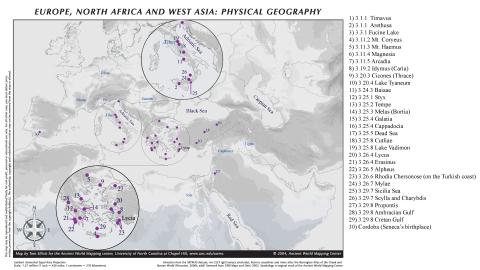

In Book 3, Seneca tours various “terrestrial waters” from lakes and rivers to springs and even underground waters. For Seneca, and many ancient thinkers, the water cycle was still only vaguely understood. They underestimated the amount of fresh water that falls as precipitation and thus found sources for terrestrial waters underground. Seneca believed the earth was porous and full of various veins and arteries of water and air. [see diagram of waters according to Seneca, by Lucy Haskell.] This helps to explain phenomena such as rivers that disappear and reappear (like the Tigris) and even earthquakes (the topic of Book 6). The karstic (limestone) landscape of much of Mediterranean leads to numerous caves and underground rivers that helped to formulate the ancient view of the Underworld, where rivers such as Styx, Cocytus, and Acheron flow (see Clendenon and Connors 2016). In this section, Seneca elaborates on this theory and utilizes an extended analogy of the earth as a human body.

[3.15.1] The earth is in certain ways like the human body.

read more

In 3.14, Seneca has written about the secret veins of water that supply the seas and are present for all major rivers. In general, ancient thinkers did not understand how much water falls from rainfall, and how rainfall and snowmelt are responsible for a majority of the volume of most rivers. Here, he expands upon the analogy that the earth is like a human body. Roby 2014 has a good discussion of the features of the analogy in this section. For more on underground rivers and the way they influenced Greek and Roman perceptions of the earth, see Baleriaux 2016.

quaedam ex istis sunt: the antecedent of istis is the conclusions of the previous chapter, which asserted the existence of hidden channels of underground water.

hoc amplius censeo: “I make this further motion,” the language of the law courts: see Hine 1996: 54–56 and Lehoux 2012: 77–105 for more on legal rhetoric in the NQ.

placet naturā regi terram: placet here = "the idea appeals to me that ..." (OLD placeo 4). Naturā here is ablative of means (AG 409) and regi is the present passive infinitive of rego regere rexi rectus, “to guide” or “rule.”

et quidem: “and what is more, (it is governed).” Suppli regi a second time. quidem preceded by et introduces a reinforcement of the previous statement (OLD quidem 5.a).

ad nostrorum corporum exemplar: ad + accusative, “according to, after.”

illae ... hae ... receptacula: “the former (are) ... the latter (are) reservoirs,” (AG 297) with veins as “reservoirs” of blood and arteries the “reservoirs” of air. Seneca asserts there are different channels for air and water, which evokes the medical theories of Praxagoras of Cos (late 4th/early 3rd century BCE). Seneca’s belief in air (spiritus) underground is also important in Book 5 (which is about wind more generally) and Book 6 (as a possible cause of earthquakes). This idea also speaks to the larger Stoic belief that the earth and the cosmos are living entities with spiritus important for connecting all living things (see Book 2). For the strong connections between Stoicism and medicine, see Hankinson 2003.

alia itinera … alia [itinera]: “some passages ... other passages” (AG 315.a)

ad similitudinem ... humanorum corporum: like ad nostrorum corporum exemplar above, this phrase expresses the close (adeo) similarity between nature and the human body.

ut ... appellaverint: “that they termed (them)” (LS appello 2, II.D), result clause (AG 537) signaled by the use of the adverb adeo in the main clause. Appellaverint is perfect subjunctive in secondary sequence after formavit (AG 482).

maiores ... nostri: “our ancestors.” Earlier writers and thinkers such as Aristotle (Problemata 935b10), Polybius (34.9.7), and Ovid (Tristia 3.7.16) spoke in this way. This manuscript of the medical writer Galen illustrates the circulatory system.

[3.15.2] Just as there are all sorts of fluids in our body, so there are many different liquids in the earth.

quemadmodum ... sic: “just as ... so,” sets up the comparison between the body and the earth.

alia necessarii alia corrupti ac pinguioris: supply umoris with the genitives (necessarii, corrupti, pinguioris) and genera with alia. Some humors are useful and pure, while others have been tainted and thickened in some way. Each type of humor in the body will shortly be seen to have an analogue in the earth.

muci, salivae ... lacrimae: plural nominative, although in English we would say “mucus, saliva, and tears.”

quiddam additum articulis: “a certain substance added to the joints.” This refers to synovial fluid, a viscous white liquid that lubricates the joints of the body. When quidam “certain” is being used as a noun (substantive) in the neuter, the form is quiddam and not quoddam (AG 151.c).

flectantur: the subject is articuli (“joints”). Subjunctive in a relative clause expressing purpose (AG 531.2).

ex lubrico: “because of the lubrication,” “as a lubricant”

[3.15.3] Certain fluids mature and harden into precious metals and stones, whereas others putrify and turn into substances like pitch.

read more

In the ancient world it was believed that minerals and metals were continually growing and able to replenish themselves (see Strabo 5.2.6, Pliny N.H. 34.165 on lead, N.H. 36.125 on marble). The Stoics maintained that elements (air, fire, water, earth) can change into one another. Seneca has given his description of this transformative potential at NQ 3.9.1–3.10.5 and it will continue to inform his idea of the water cycle as the work continues. There may be a larger parallelism about the search for wealth that avaritia encourages (he elsewhere connects mining with avaritia, see Selection 6), and the search for knowledge of the natural world, which also necessitates some “digging” (eruere, 3.pr.1). In general, Seneca denigrates the workings of greed and endorses the pursuit of wisdom, a grander goal than mere aurum argentumque.

quae ... durentur: relative clause of characteristic (AG 535).

matura: “when mature.” The imagery here with fructus endows waters with a life cycle.

quibus: the antecedent of this relative pronoun is metallorum.

petit ... avaritia: “greed seeks.” Note the personification. Moralistic disapproval of the mining of precious metals is traditional. See Ov. Metamorphoses 1.137–140 and Sen. NQ 3.30.3 and 5.15.1–4.

quae ... vertuntur: these could refer to magma and probably to quartz (at NQ 3.25.12 Seneca writes how such rock crystal is hyper-cooled water, which Pliny the Elder supports at N.H. 36.2). But Seneca may also be thinking of other metals that are quarried, but then able to be melted (and turned back to liquid).

bitumen: “pitch” which is a sticky, black, highly viscous form of petroleum. Many ancient thinkers discussed its nature (e.g. Herodotus 1.179, Pliny N.H. 2.235–237, Ovid Metamorphoses 15.350).

huic similia: similis takes the dative (AG 385).

causa aquarum... nascentium: aquarum ... nascentium is an objective genitive (AG 348) dependent on causa. The entire sentence sums up the belief that waters are born underground according to the plan or will of nature. This is orthodox Stoicism, with god (a.k.a. nature) controlling everything by a fixed set of laws.

lēgem ... voluntātemque: “the law and will,” accusative after the preposition secundum, “according to.”

[3.15.4] Sometimes the liquids in the earth acquire faults or are contaminated, just like the fluids in our bodies. External causes can influence the quality and rhythm of such fluids.

ut ... ita: “just as ... so”

loci senium: “exhaustion of the soil,” note the personification of the earth as old.

corrupēre naturam: “damages its natural quality.” corrupēre = corrupērunt. This and contraxit below are perfect used for a general truth (AG 475). The various forces mentioned could apply to the earth or to the body (e.g. quassatio is used of earthquakes at NQ 3.11.1, but also of the trembling that accompanies fever at Ep. 95.17).

suppuratio contraxit umorem: the festering sore (suppuratio) has “caused fluid to collect” (contraxit) in this spot. Contraho is utilized to describe the collection of fluids in the body (OLD 4d). The manuscripts reading sulphuratio instead of suppuratio should be dismissed because, in the words of Hine, “from the ancient point of view there is no sulphur in the human body, and anyway how is sulphur in the earth meant to assist the condensation of liquid there?” (1980: 195)

qui: “(a condition) which,” referring to the process of condensation.

modo... modo: “at one time ... at another” or “now ... now” (AG 323)

[3.15.5] Sometimes rivers emerge from fissures in the earth, like blood from a cut.

ut ... ita: “just as ... so”

tam diu ... donec: “so long ... until.” Donec + perfect indicative denotes an actual fact in past time (AG 554).

<coeunte> venae scissura: coeunte is a conjecture by Hine, creating an ablative absolute (AG 419) that expresses how the flow abates.

interclus<us> est: Watt’s emendation. The verb describes how the blood flow is blocked.

retro dedit sanguinem: “it has sent the blood back.”

rivus: rivus denotes a stream or brook, whereas flumen is used of larger rivers.

[3.15.6] Some of these earth-born streams stop flowing at times, for various reasons.

read more

The size of the river depends on the size of the underground vein, its own supplies of water, and its ease of movement. Again, comparisons with the human body make the earth into a living being. D. Furley says of this analogy: “The decision to view the cosmos as a living creature may be regarded as the foundation of Stoic cosmology. We can guess at the reasons that made it an attractive picture. Like living organisms, the cosmos is a material body endowed with an immanent power of motion. It consists of different parts, which collaborate towards the stable functioning of the whole, each part performing its own work. The relation of the parts to each other and to the whole exhibits a kind of fitness, not always obvious in detail indeed, but unmistakable in the larger picture. This sense of fitness suggests rationality: it is an easy inference that the cosmos itself is possessed of reason, and since reason is a property confined to living creatures, this again suggests that the cosmos is a living being” (Furley 2005, 436).

interest: "it makes a difference" (LS intersum III).

quanta aperta sit vena: the verb is subjunctive in an indirect question (AG 574).

consumptā aquā: ablative absolute (AG 419).

excaecatur aliquo impedimento: such a blockage evokes the teaching of Asclepiades of Bithynia who believed all disease was caused by blockages in veins and arteries.

read more

The verb excaecare is also found in a speech of Ovid’s Pythagoras about water (Metamorphoses 15.272) and may be a direct allusion, since Seneca draws upon Ovid’s Pythagoras at other times in Book 3 (see Garani 2020). Such echoes of Augustan poetry are common in Seneca’s prose and poetry, and help him to further explain his points and connect his writings with those of the previous generation.

velut in cicatricem: “as if into a scar,” repeating the idea in 3.15.5, but now the flow is completely blocked.

comprimitque quam perfecerat viam: i.e., et comprimat (eam) viam quam perfecerat. Seneca’s word order emphasizes viam.

quam esse mutabilem diximus: quam has terra as antecedent.

alimenta: “ingredients,” “raw material.” Seneca had written about the way the earth can change into water at 3.9.3 (placet nobis terram esse mutabilem). Here it almost seems like a process of digestion and excretion.

desinit: desino -ere can take a complementary infinitive, here posse (AG 456).

[3.15.7] Water can be created underground in various ways. This helps to explain how certain springs, once dormant, can become active again.

per se: “by itself”

adposita plenis: the compound verb takes the dative case (AG 370). This may refer to osmosis, and the famous description of it in Plato’s Symposium (175d4–e2), or the siphoning of water from one place to another.

facilis in tabem: “prone to decay.” Again, words that are commonly used for the body are applied to the earth.

idem ... quod: “the same thing ... which.” Seneca stresses that conditions and topography underground match the upper world. As he will write at NQ 3.16.4: “believe whatever you see above is below as well” (crede infra quidquid vides supra).

ut spissetur <aër>: the conjecture is from Haase and is paralleled at NQ 2.30.4; spissetur is subjunctive in a substantive clause of result (AG 568).

gravior quam ut ... possit: “too heavy to be able.” gravior modifies aër.

roris modō: “in the manner of dew,” “like dew” (LS modus II.B.2)

sudor aquileges vocant: the methods of water-finders are discussed by Vitruvius (8.1.1–7). The fact that they call this sort of water “sweat” furthers the world/body analogy, as does the way in which such water reacts to heat and pressure.

vel pessurā loci ... vel aestū: vel ... vel (“either... or”) connects two ablatives of means (AG 409).

[3.15.8] Large underground reservoirs produce substantial rivers, which can burst forth with immense force and volume.

This will be problematic for the human race during the flood at the end of this book. At 3.27.1 Seneca says, “the earth will unleash more rivers and open up new springs” to inundate the land.

haec tenuis unda: refers back to the sudor in 3.15.7.

nonnumquam ... nonnumquam: “sometimes ... sometimes.”

emissi: modifies amnes.

illam spiritus intermixtus eiecit: the antecedent of illam is aqua. Seneca wrote how spiritus influences water at NQ 3.3.1, and he writes how a discharge of air is accompanied by sound (cum sono) at NQ 5.4.2.

vocabulary

adsentiō –īre –sēnsī –sēnsus: to agree with, assent, approve (+ dat.)

placet placere placuit (+ dat.): it is pleasing to [me], I decide

exemplar exemplāris n.: likeness, model, exemplar, image

vēna vēnae f.: vein, channel

artēria –ae f.: windpipe; artery

receptāculum –ī n.: deposit, reservoir, receptacle

similitūdō similitūdinis f.: likeness

fōrmō fōrmāre fōrmāvī fōrmātus: to form, shape

appellō –ere –pulī –pulsus: to drive to; bring

vēna vēnae f.: vein, channel

ūmor –oris m.: moisture, liquid

necessārius –a –um: necessary, essential 3.15.2

corruptus –a –um: tainted, rotten, impure

pinguis pingue: thick, dull

cerebrum –ī n.: brain

mūcus mūcī m.: mucus, snot

salīva salīvae f.: saliva

medulla medullae f.: marrow

articulus articulī m.: joint

cito citius (comp.) citissime (superl.): quickly

flectō flectere flēxī flexus: to bend

lūbricus –a –um: slippery, lubricated

ūmor –oris m.: moisture, liquid

complūrēs complūrium: many, several

mātūrus –a –um: mature 3.15.3

dūrō dūrāre dūrāvī dūrātus: to endure, hold out, harden

hinc: from this source/cause

metallum –ī n.: metal, mine

avāritia avāritiae f.: greed

līquor līquōris m.: a fluid, liquid

ūmor –oris m.: moisture, liquid

putrēscō –ere –truī —: rot, putrefy

bitūmen –inis n.: pitch, asphalt.

secundum: according to, following

ūmor –oris m.: moisture, liquid 3.15.4

concipiō concipere concēpī conceptum: conceive, catch, draw

quassātiō –ōnis f.: violent shaking

senium –ī n.: condition of old age

frīgus frīgoris n.: cold, chill

aestus aestūs m.: heat; tide, seething, raging (of the sea)

suppūrātio (subp–) –ōnis f.: festering sore, abscess

contrahō contrahere contrāxī contractus: to collect; shrink because of pain

diūturnus –a –um: lasting, lasting long

percutiō percutere percussī percussum: to pierce, lance; strike, beat 3.15.5

vēna vēnae f.: vein, channel

mānō mānāre mānāvī mānātus: to flow, pour, be shed. Not to be confused with maneo -ēre

effluō –ere –xī: to flow out, slip away

coeō coīre coīvō/coiī coitus: to come together, combine, unite

scissūra –ae f. : fissure, cut

subsīdō –ere –sēdī –sessus: to sink, subside, settle

interclūdō –ere –clūsī –clūsus: cut off, blockade, hinder, block up

retrō: backwards

patefaciō patefacere patefēcī patefactum: open up, expose

rīvus –ī m.: brook, stream

ex–caecō –āre: to block a channel, blind 3.15.6

impedīmentum impedīmentī n.: impediment, hindrance

coeō coīre coīvō/coiī coitus: to come together, combine, unite

cicātrīx –īcis f.: scar, bruise

comprimō comprimere compressī compressum: to press together, check, curb

perficiō perficere perfēcī perfectus: to accomplish, perfect

mūtābilis –e: changeable, fickle

alimentum –ī n.: food, fuel, provisions

ūmor –oris m.: moisture, liquid

aliquando: sometimes 3.15.7

exhauriō exhaurīre exhausī exhaustum: to drain out, empty out, remove

repleō –ēre –plēvī –plētus: to fill, fill again

recolligō recolligere recollēgī recollectum: to gather again, collect

aliunde: from elsewhere, from another place/source

trānsferō trānsferre trānstulī trānslātus: to transfer, carry over/across

inānis inānis ināne: empty, void

appōnō –pōnere –posuī –positus: to place near; appoint

ūmor –oris m.: moisture, liquid

āvocō –āre: to divert, remove, take away

tābēs –is f.: decay, putrefaction, wasting away

(h)ūmēscō ūmēscere — —: to become wet/moist

ēveniō ēvenīre ēvēnī ēventus: happen, turn out

nūbēs nūbis f.: cloud, mist

spissō –āre : to thicken, condense

rōs rōris m.: dew

tenuis tenue: thin

dispergō –ere –spersī –spersus: to scatter, disperse, disperse

līquor līquōris m.: a fluid, liquid

cōnfluō –fluere –flūxī —: to flow together, run together

sūdor sūdōris m.: sweat

aquilex –egis/–icis m.: water diviner, man used to find water

gutta guttae f.: drop

pressūra –ae f.: pressure, weight

ēlīdō –ere –līsī –līsus: strike/knock out, send forth, expel

aestus aestūs m.: heat; tide, seething, raging (of the sea)

ēvocō ēvocāre ––– ēvocātus: to call forth, summon, evoke

tenuis tenue: thin 3.15.8

sufficiō sufficere suffēcī suffectum: be sufficient for (+dat.), suffice

caverna –ae f.: hollow; cavern

conceptus –ūs m.: cistern, basin, reservoir

excidō excidere excidī: fall out, escape

nōnnumquam: sometimes

ēmittō ēmittere ēmīsī ēmīssus: let go, send out, cast, expel

vehemēns –ntis: violent

sonus sonī m.: sound

intermisceō –miscēre –miscuī –mixtum : to intermix

ēiciō ēicere ēiēcī ēiectus: eject, expel, shoot forth