[7.27.1] ‘Quārē?’ inquis. dīc tū mihi prius quārē lūna dissimillimum solī lūmen accipiat, cum accipiat ā sōle; quārē modo rubeat, modo palleat; quārē līvidus illī et āter color sit cum cōnspectū sōlis exclūditur. [7.27.2] dīc mihi quārē omnēs stēllae inter sē dissimilem habeant aliquātenus faciem, dīversissimam sōlī. quōmodo nihil prohibet ista sīdera esse, quamvīs similia nōn sint, sīc nihil prohibet comētās aeternōs esse et sortis eiusdem cuius cētera, etiamsī faciem illīs nōn habent similem. [7.27.3] quid porrō? mundus ipse, sī cōnsīderēs illum, nōn ex dīversīs compositus est? quid est quārē in Lēōne sōl semper ārdeat et terrās aestibus torreat, in Aquāriō adstringat hiemem, flūmina gelū claudat? et hoc tamen et illud sīdus eiusdem condiciōnis est, cum effectū ac nātūrā dissimile sit. intrā brevissimum tempus Ariēs extollitur, Lībra tardissimē ēmergit. et hoc tamen sīdus et illud eiusdem nātūrae est, cum illud exiguō tempore ascendat, hoc diū prōferātur. [7.27.4] nōn vidēs quam contrāria inter sē elementa sint? gravia et levia sunt, frīgida et calida, ūmida et sicca; tōta haec mundī concordia ex discordibus cōnstat. negās comētēn stēllam esse, quia fōrma eius nōn respondeat ad exemplar nec sit cēterīs similis? vidēs enim: simillima est illa quae trīcēsimō annō revertitur ad locum suum huic quae intrā annum revīsit sēdem suam. [7.27.5] nōn ad ūnam nātūra fōrmam opus suum praestat, sed ipsā varietāte sē iactat: alia maiōra alia vēlōciōra aliīs fēcit, alia validiōra, alia temperātiōra, quaedam ēdūxit ā turbā, ut singula et cōnspicua prōcēderent, quaedam in gregem mīsit. ignōrat nātūrae potentiam quī illī nōn putat aliquandō licēre nisi quod saepius fēcit. [7.27.6] comētās nōn frequenter ostendit, attribuit illīs alium locum, alia tempora, dissimilēs cēterīs mōtūs: voluit et hīs magnitūdinem operis suī colere. quōrum fōrmōsior faciēs est quam ut fortuitam pūtēs, sīve amplitūdinem eōrum cōnsīderēs sīve fulgōrem, quī maior est ārdentiorque quam cēterīs. faciēs vērō habet īnsigne quiddam et singulāre, nōn in angustum coniecta et artāta, sed dīmissa līberius et multārum stēllārum amplexa regiōnem.

[7.28.1] Aristotelēs ait comētās significāre tempestātem et ventōrum intemperantiam atque imbrium. quid ergō? nōn iūdicās sīdus esse quod futūra dēnūntiat? nōn enim sīc hoc tempestātis signum est quōmodo futūrae pluviae 'scintillāre oleum et putrēs concrēscere fungōs,' aut quōmodo indicium est saevītūrī maris, sī

'marīnae

in siccō lūdunt fulicae nōtāsque palūdēs

dēserit atque altam suprā volat ardea nūbem,'

sed sīc, quōmodo aequinoctium in calōrem frīgusque flectentis annī, quōmodo illa quae Chaldaeī canunt, quid stēlla nāscentibus trīste laetumve cōnstituat. [7.28.2] hoc ut sciās ita esse, nōn statim comētēs ortus ventōs et pluviās minātur, ut Aristotelēs ait, sed annum tōtum suspectum facit; ex quō appāret illum nōn ex proximō quae in proximum daret signa trāxisse, sed habēre reposita et comprēnsa lēgibus mundī. [7.28.3] fēcit hic comētēs quī Paterculō et Vopiscō cōnsulibus appāruit quae ab Aristotele Theophrastōque praedicta <sunt>; fuērunt enim maximae et continuae tempestātēs ubīque, at in Achāiā Macedoniāque urbēs terrārum mōtibus prōrutae sunt.

[7.29.1] ‘Tarditās’ inquit, ‘illōrum argūmentum est graviōrēs esse multumque in sē habēre terrēnī, ipse praetereā cursus: ferē enim compelluntur in cardinēs.’ utrumque falsum est. dē priōre dīcam prius. quid? quae tardius feruntur gravia sunt? quid ergō? stēlla Sāturnī, quae ex omnibus iter suum lentissimē efficit, gravīs est? atquī levitātis argūmentum habet quod suprā cēterās est. [7.29.2] ‘sed maiōre’ inquis, ‘ambitū circuit nec tardius it quam cēterae sed longius.’ succurrat tibi idem mē dē comētīs posse dīcere, etiamsī sēgnior illīs cursus sit. sed mendācium est īre eōs tardius; nam intrā sextum mēnsem dīmidiam partem caelī trānscurrit hic proximus, prior intrā pauciōrēs mēnsēs sē recēpit. [7.29.3] ‘sed quia gravēs sunt, īnferius dēferuntur.’ prīmum nōn dēfertur quod circumfertur. deinde hic proximus ā septentriōne mōtūs suī initium fēcit et per occidentem in merīdiāna pervēnit ērigēnsque cursum suum oblituit; alter ille Claudiānus, ā septentriōne prīmum vīsus, nōn dēsiit in rēctum assiduē celsior ferrī, dōnec excessit.

Haec sunt quae aut aliōs movēre ad comētās pertinentia aut mē: quae an vēra sint, dīī sciunt, quibus vērī scientia est. nōbīs rīmārī illa et coniectūrā īre in occulta tantum licet, nec cum fīdūciā inveniendī nec sine spē.

[7.30.1] Egregiē Aristotelēs ait numquam nōs verēcundiōrēs esse dēbēre quam cum dē dīīs agitur. sī intrāmus templa compositī, sī ad sacrificium accessūrī vultum submittimus, togam addūcimus, [sī] in omne argūmentum modestiae fingimur, quantō hoc magis facere dēbēmus, cum dē sīderibus, dē stēllīs, dē deōrum nātūrā disputāmus, nē quid temere, nē quid impudenter aut ignōrantēs adfirmēmus, aut scientēs mentiāmur! [7.30.2] nec mīrēmur tam tardē eruī quae tam altē iacent. Panaetiō et hīs quī vidērī volunt comētēn nōn esse ōrdinārium sīdus sed falsam sīderis faciem dīligenter tractandum est an aequē omnis pars annī edendīs comētīs satis apta sit, an omnis caelī regiō idōnea in quā creentur, an, quācumque īre, ibi etiam conspicī possint, et cētera. quae ūniversa tolluntur, cum dīcō illōs nōn fortuitōs esse ignēs sed intextōs mundō, quōs nōn frequenter ēdūcit sed in occultō movet.

[7.30.3] Quam multa praeter hōs per sēcrētum eunt numquam hūmānīs oculīs orientia! neque enim omnia deus hominī fēcit. quota pars operis nōbīs committitur! ipse quī ista tractat, quī condidit, quī tōtum hoc fundāvit deditque circā sē, maiorque est pars suī operis ac melior, effugit oculōs: cōgitātiōne vīsendus est. [7.30.4] multa praetereā cognāta nūminī summō et vīcīnam sortīta potentiam obscūra sunt, aut fortasse, quod magis mīrēris, oculōs nostrōs et implent et effugiunt, sīve tanta illīs subtīlitās est quantam cōnsequī aciēs hūmāna nōn possit, sīve in sānctiōre sēcessū maiestās tanta dēlituit et rēgnum suum, id est sē, regit, nec ūllī dat aditum nisi animō. quid sit hoc sine quō nihil est scīre nōn possumus; et mīrāmur, sī quōs igniculōs parum nōvimus, cum maxima pars mundī, deus, lateat!

[7.30.5] Quam multa animālia hōc prīmum cognōvimus saeculō, quam multa [negōtia] nē hōc quidem! multa venientis aevī populus ignōta nōbīs sciet; multa saeculīs tunc futūrīs cum memoria nostrī exolēverit reservantur. pusilla rēs mundus est nisi in illō quod quaerat omnis mundus habeat. [7.30.6] nōn semel quaedam sacra trāduntur: Eleusīn servat quod ostendat revīsentibus; rērum nātūra sacra sua nōn semel trādit. initiātōs nōs crēdimus? in vestibulō eius haerēmus. illa arcāna nōn prōmiscuē nec omnibus patent; reducta et interiōre sacrāriō clausa sunt, ex quibus aliud haec aetās, aliud quae post nōs subībit aspiciet.

notes

Selection 9 (7.27.1–7.30.1–6): Conclusion of comet doxography and analysis of Aristotle’s view on comets.

Seneca wraps up his book on comets by asserting that comets are actually stars whose orbits are exceptionally long. This differs from some prevailing theories, including those of Aristotle and the Stoic thinker Panaetius, and Seneca discusses their views critically. As is typical of his method, Seneca engages with earlier writers while showing independence of thought and making larger connections to the nature of science more generally.

Further Reading: For Seneca’s view of scientific progress, see Tutrone 2014. For a short overview on ancient astronomy in general, see Taub 2020.

[7.27.1] The moon’s light has a single source, yet is various.

‘Quare?’ inquis: Seneca has just asserted that comets are in fact stars of an unusual type. He imagines a skeptical interlocutor asking why this should be so.

prius: “before (I answer your question),” “first”

quare ... lumen accipiat, cum accipiat: “why (the moon) takes on light ..., although it receives (it).” The first clause is indirect question after dic mihi, the second a concessive cum-clause. Both subjunctives are to be translated as indicative in English, as are all the following indirect questions. The Stoics accepted that the moon’s light came from the sun.

modo ... modo: “at some times ... at others”

[7.27.2] Stars have different appearances, so why shouldn’t comets be eternal like stars, even though they look so different?

soli: dative after diversissimam (AG 384)

quomodo ... sic: “just as ... so”

prohibet ista sidera esse: “prevents those things from being stars”

quamvis … non sint: “although they are not” (AG 527)

sortis eiusdem cuius cetera: “in the same category to which the rest (belong).” The genitives are of quality (AG 345) or partitive (AG 346).

[7.27.3] Constellations can be quite different in their behavior, despite being made of the same stuff.

Seneca provides information about constellations rising at their own particular times of the year. This would be the heliacal rising and would differ slightly from our own calendar dates. Pliny gives dates for certain winter constellations at N.H. 18.234-37 and there were jokes told about Caesar's new calendar and the constellations rising by Caesar's fiat (Plutarch Caesar 59.3). See Hannah 2009 for more on conceptions of time in antiquity.

quid porro?: “what else?” “what further?” introducing a rhetorical question, as at 3.30.2.

si consideres illum: the protasis of a future more vivid condition (AG 516) with a rhetorical question in the apodosis. Such engaging touches help to make the reader actively participate with the ideas of the text.

quid est quare: “why is it that?” introducing indirect questions with the subjunctive.

in Leone: the constellation Leo rises on July 22.

in Aquario: the constellation Aquarius rises on January 20.

adstringat hiemem: “tightens winter’s grip”

sidus: “constellation”

eiusdem condicionis: genitive of quality (AG 345)

cum … dissimile sit: concessive cum-clause (AG 549)

extollitur: “rises,” a middle use of the passive voice. The same idea is expressed shortly by the synonyms emergit, ascendat, and proferatur.

exiguo tempore: “within a very short time” (AG 423), varying intra brevissimum tempus in the corresponding place in the previous sentence.

Note the elaborate balancing of these clauses. The emphasis lies on the tamen clauses, with anaphora.

[7.27.4] To expect perfect uniformity among stars is to ignore the extreme contrasts characteristic of the universe.

The world is made up of opposing elements of varying temperatures, weights, and wetness. The balance of opposites was a topic of scientific concern from the Presocratics to Seneca’s own day. If comets return to the same spot of the sky every thirty years, they are very similar to stars which return to the same spot annually.

quam contraria: “how contrasting,” an indirect question (AG 586)

tota haec mundi concordia ex discordia constat: resembles Horace’s rerum concordia discors (Ep. 1.12.19) as well as Ovid’s discors concordia (Met. 1.433).

constat: “is formed” (LS consto II.B.5)

quia … respondeat … nec sit: quia + subjunctive indicates that the reason given is not vouched for by the speaker (AG 540).

vides enim: “consider this” (LS video II.B.1).

illa ... huic: “that (comet) ... to this (comet).” huic is dative after simillima. Comets can have very different frequencies of appearance and still be comets.

[7.27.5] Nature delights in variety.

The personification of nature as a kind of creative artist is seen also in Lucretius, who writes rerum natura creatrix (1.629, 2.1117, 5.1362), and in Seneca’s tragedy Phaedra (959).

ad unam ... formam: “according to one pattern”

se iactat: “she shows off by” or “boasts about” + ablative, varietate. Seneca personifies Nature as an author or artist whose work (opus) is full of variety.

ut singula et conspicua procederent: “so that they might crop up as unique and conspicuous things” (OLD procedo 6).

ignorat: “(that man) does not understand.” The subject is described in the following relative clause, qui non putat ....

qui illi non putat aliquando licere nisi quod saepius fecit: “who does not think that she (Nature) is allowed (to do) occasionally (something) unless (it is something) which she has done more frequently.” That is, not everything Nature does happens frequently; comets can be rare and still be stars. illi is the expected dative after licere and is emphasized by its position.

[7.27.6] Comets are too beautiful and impressive to be accidental.

Nature produces comets as an example of something special. Seneca had opened this book by claiming that such rare phenomena get the attention of observers and philosophers. Comets are not formed by chance, but have a specific time, place, and shape.

ceteris: “to all the other (stars),” dative, instead the more common genitive after dissimilis (AG 385).

et his: “with these also,” i.e. comets.

magnitudinem operis sui colere: “to adorn the majesty of her work” (LS colo II.A.3).

quorum formosior facies est quam ut fortuitam putas: “their appearance is too beautiful to think them accidental,” a result clause after a comparative (AG 535b).

facies vero habet insigne quiddam et singulare: “Moreover, their appearance has a kind of exceptional distinction.”

in angustum coniecta et artata: “thrust and squeezed into a narrow space”

[7.28.1] According to Aristotle comets can indicate changes in weather (as other celestial phenomena do)—not immediate changes, but those affecting the character of an entire year.

In his Meteorology (Book 1, Part 7) Aristotle proposes that comets are exhalations of the atmosphere that burst into flame; they can accompany stars or be generated by stars, but are not themselves stars; when frequent, they foreshadow wind and drought over the course of a whole year (“So when there are many comets and they are dense, it is as we say, and the years are clearly dry and windy”). Many other thinkers, including the Stoics, believed that comets were produced by atmospheric conditions (see 7.4.2–7.10.3 for Epigenes’ belief that comets formed in the atmosphere, and 7.19.1–7.21.4 for Stoic ideas).

tempestatem: “stormy weather” (LS tempestas II.A.2)

intemperantiam: “an excess of” + gen.

sidus esse quod futura denuntiat: “(that) which foretells the future is a celestial body.” sidus is emphasized by it position, and is the main point, since Seneca is arguing that comets are in fact sidera. Most philosophical systems (and most Romans) believed in astrology. If comets have prophetic power like that of stars, argues Seneca, they must be stellar in nature (and not atmospheric fires). During the Augustan period Manilius wrote a detailed Stoic explication of astrology, the Astronomica. Barton 1994 is a fine account of ancient astrology.

non ... sic ... quomodo: “not in the same way ... as.” Seneca compares the comet (hoc) as a predictor of weather to other, non-celestial, weather signs, such as the behavior of oil lamps and marsh birds, described just below.

futurae pluviae: supply signum est.

scintillare ... fungos: “the oil (lamp) sputters and a mouldy fungus gathers on the wick.” This is a quotation of Vergil’s Georgics 1.392, where these characteristics of the lamp indicate impending rain. The “fungus” may also refer to mushroom-shaped puffs of smoke rising from the wick.

read more

Note that Vergil’s didactic work is granted the same truth value as Seneca’s own work (and that of more traditional philosophers), showing how poets belong to Seneca’s community of scholars. Elsewhere, however, Seneca writes that Vergil in his Georgics “looked to write not what was most truthful, but what was most pleasing, and did not want to teach farmers but to delight readers” (Ep. 86.15). It is clear that the great works of his Augustan predecessors could be wielded in different manners, depending on Seneca’s larger argument and the genre of his work.

marinae ... fulicae: the Eurasian coot (Fulica atra), a member of the rail and crake bird family common in Europe. They can be seen swimming on open water or walking across waterside grasslands.

in sicco … nubem: another quotation of Vergil’s Georgics (1.363–4). Prophecy by bird signs, or auspicium, was an important aspect of Roman religion; it is true that their behavior can foretell the weather—just think of geese flying south in the winter.

ardea: probably the grey heron (Ardea cinerea), which is native throughout Europe.

sed sic: supply signum est from above.

aequinoctium: supply signum est.

aequinoctium ... flectentis anni: take the prepositional phrase after flectentis. At each equinox the year “turns,” either towards heat (Spring) or cold (Autumn).

Chaldaei: the Chaldaeans were a people of Assyria famous for their astrological prowess, so Chaldaei came to mean “astrologers, soothsayers.” In NQ 3.29.1, Seneca mentions the ability of the astrologer Berossus to foretell the coming of a flood.

quid ... triste laetumve: direct objects of constituat. stella is the nominative subject.

constituat: “ordains,” “appoints”

[7.28.2] The fact that comets indicate the suspect character of an entire year shows that they are part of the larger universe, not casual atmospheric phenomena.

ut scias: purpose clause (AG 531)

cometes ortus: the appearance of a comet

ut Aristoteles ait: this phrase applies to non statim. Seneca accurately reports Aristotle’s view that comets are not signs of immediate changes in the weather, but affect the prevailing climate (Meteorology Book 1, Part 7).

illum … signa traxisse: “it (the comet) has not drawn from its immediate neighborhood signs which it gives for the immediate future” (Corcoran). quae in proximum daret is a relative clause of purpose (AG 531.2).

habere reposita et comprensa legibus mundi: “it has them stored up and linked to the laws of the universe.”

[7.28.3] A recent example proves Aristotle’s point.

fecit ... quae: “did (the things) which.” hic cometes is the subject of fecit, which is emphasized by its initial position, virtually = “did in fact do....”

Paterculo et Vopisco consulibus: 60 CE. The comet in that year (when C. Velleius Paterculus and M. Manilius Vopiscus were suffect consuls) coincided with storms and earthquakes in Greece. That Greek earthquake is important when trying to decide whether the earthquake at Pompeii occurred in 62 or 63 CE (see 6.1.13 and Wallace-Hadrill 2003: 180–82).

[7.29.1] The slow movement of comets is no proof that they are heavier than stars and terrestrial in nature.

inquit: the interlocutor sometimes is 2nd person (as at 7.29.2 below), at other times, 3rd person (i.e. “someone states”); the 3rd person here may present the scientific views of other schools, rather than an opinion that Lucilius himself may espouse.

argumentum est ... esse: “is proof that they are”

multumque ... terreni: terreni is partitive genitive with multum (AG 346).

in cardines: “toward the poles.”

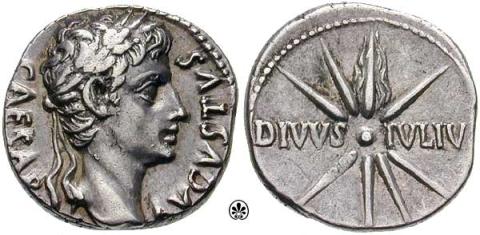

stella Saturni: the planet Saturn takes twenty-nine years to complete an orbit of the sun, and its orbit in the night sky takes it higher than the other planets. Saturn is the furthest planet that can be seen without the aid of telescopes (as noted in Ptolemy’s spheres seen in this illustration).

atqui: “and yet,” marking a strong antithesis.

quod ... est: “the fact that it is.” This clause is the subject of habet.

[7.29.2] Comets in fact move faster than other stars, not more slowly.

circuit: stella Saturni is the subject.

tardius ... quam ceterae: quam with the comparative (AG 407)

succurrat tibi: “it should occur to you that” (LS succurro II.B)

idem me ... posse dicere: “that I can say the same thing.” The same point that helps the interlocutor make his argument will help Seneca as well.

mendacium est: this introduces the indirect statement with eos, the accusative subject of ire (AG 577).

intra sextum mensem: “within the sixth month,” i.e. within six months.

hic proximus: this must mean the comet of 60 CE, the most recent one. Pliny the Elder notes the large number of comets during Nero’s reign (N.H. 2.92).

prior ... recepit se: “the earlier one withdrew.” The previous comets have completed their appearance in even fewer months.

[7.29.3] Comets move in orbits; they do not fall downwards. The most recent ones actually rose. But these matters are speculative and uncertain.

primum ... deinde: “first of all ... furthermore”

quod circumfertur: “that which is carried around,” subject of defertur.

a septentrione: the North Star is part of the constellation, the Great Bear. The recent comet moved from the North to the West until it reached the South and then disappeared as it was rising.

motus sui initium: “the beginning of its movement” through the sky.

alter ille Claudianus: according to Suetonius (Claudius 46) this comet, which appeared in 54, was looked upon as an omen that foretold the emperor Claudius’ death in that year. See Rogers 1953 for more on the comets from 54–64 CE.

desiit: pf. act. > desino, “cease,” with the complementary infinitive, ferri (AG 456).

haec ... me: “these are the things pertaining to comets which have impressed others, or made an impression on me” (LS moveo I.B).

an vera sint: indirect question introduced by dii sciunt (AG 574). Only the gods know what is true.

quibus: dative of possession (AG 373).

nobis ... licet: licet takes the dative + infinitive, as normal (AG 368).

tantum: “merely”

nec cum fiducia inveniendi nec sine spe: one is not guaranteed a discovery, but there will be hope for one.

[7.30.1] In matters of astronomy we must be cautious and modest in our assertions.

Aristotle says we should show humility when discussing or worshipping the gods. This is all the truer of science. Our knowledge is limited, and we should seek to make as few false statements about nature as we can.

egregiē Aristotles ait: not in any of his preserved works. This is Aristotle, frag. 14 (Rose).

verecundiores … quam: comparative adjective with quam (AG 407).

debēre: infinitive in indirect speech with nos as its accusative subject (AG 580).

cum de diis agitur: “when the gods are involved”

compositi: “calm,” “orderly.” Romans showed respect for the gods by maintaining order, lowering their gaze and wearing their finest clothing when going to the temples and performing religious rites.

togam adducimus: gathering up the toga, rather than letting it flow free, was evidently a sign of modesty or humility. adducimus = contrahimus.

in omne argumentum modestiae fingimur: “we assume every sign of modesty,” literally “we are formed into,” i.e., we take on as a product of habit and training (see LS fingo II.B.2).

quanto hoc magis: ablative of degree of difference paired with the ablative of comparison (AG 414). If going to the temples requires correct decorum, it is even more important to show restraint when speaking about the works of the gods. There is an interesting distinction between language and action here, with Seneca stressing that one must always strive to speak as truthfully as possible about divine matters.

ne… .ne… : negative purpose clauses (AG 531); quid stands for aliquid after ne.

[7.30.2] Panaetius’ view is that comets are not stars but fortuitously created pseudo-stars. But this raises several questions that do not arise if we see them as actual stars that are simply hidden most of the time.

We shouldn’t be surprised that the truth is hard to discover. We must analyze all aspects of the comet’s nature: orbits, frequency, appearance, and disappearance. One thing is sure, they are not random events, but rather part of the divine plan of nature (and thus follow larger Stoic, not Epicurean, tenets). This passage evokes the opening of the work as a whole (see Selection 1). For such hidden knowledge as part of the plan of the Stoic Zeus, see Aratus Phaen. 768–71: “For we humans have not yet acquired knowledge of everything from Zeus, there is much still hidden from us that Zeus, if he wishes, will make manifest at a later date.”

miremur: hortatory subjunctive (AG 439).

tam tarde erui quae tam alte iacent: take the relative clause first, “that (things) which lie hidden so deeply take so long to be discovered.” The language evokes the opening of the treatise (NQ 3.pr.1).

Panaetio et his … diligenter tractandum est: “it must be meticulously argued by Panaetius and those who… ”; the passive periphrastic takes the dative case (AG 374). Panaetius was the Stoic philosopher responsible for making Stoicism popular in Rome in the 2nd century BCE. Seneca dissents from the views of Panaetius here, although in other works he says that Panaetius is a fine thinker (Ep. 116.5–6).

an … an … an: “whether… or… or”; the anaphora of an introduces these indirect questions, hence the verbs in the subjunctive (AG 574).

edendis cometis: “for producing comets,” dative after apta.

an, quacumque ire, ibi etiam conspici possint: “or whether they can also be perceived wherever they can go.”

quae universa tolluntur: “all of which [questions] are removed.” Panaetius’ questions are rendered irrelevant.

intextos mundo: “interwoven into the universe” like stars, rather than created separately.

educit … movet: the subject is mundus, which is personified to be like a god/natura.

in occulto: “secretly,” or perhaps “in the darkness” (of space). Again, this seems to evoke the opening of the work as a whole, where Seneca wants to perceive “things so hidden” (tam occulta, NQ 3.pr.1).

[7.30.3] The majority of natural phenomena are never seen by humans and must be perceived through thought.

Echoing standard Stoic view, Seneca argues that the God who created and manages the world is somehow hidden, though he is all around us. This looks forward to the preface of the following book (see Selection 10) and reinforces the idea that comets can be part of the grand machinery of the universe, yet invisible to us most of the time.

quam: introducing an exclamation (AG 269.c)

praeter hos: in addition to comets, which are usually invisible to humans

homini: “for the benefit of humans.” The universe is providential from the point of view of God, not the point of view of mankind. Elsewhere Senecas says, “I will know everything is small after I have measured God” (sciam omnia angusta esse, mensus deum, NQ 1.pr.17).

ipse: God

quota pars: “how very small a part”

tractat: “manages”

ista: the universe

dedit ... circa: “placed it around” = circumdat.

qui totum hoc fundavit: this is similar to what Seneca writes in the preface of Book 1. See 1.pr.13: “What is god? He is all that you see and all that you do not see” (quid est deus? Quod vides totum et quod non vides totum).

effugit oculos: the true conception of God is discovered with the mind, not the eyes. See Hadot 2004 on this aspect of the Stoic concept of Natura.

cogitatione visendus est: cogitatione is ablative of means with this passive periphrastic construction (AG 193). This cogitatio is what Seneca encourages and models throughout the Naturales Quaestiones.

[7.30.4] Even the god who is the universe is beyond our sense perception; it is unsurprising that we don’t fully perceive comets.

cognata numini summo: “related to the highest divinity”

vicinam sortita potentiam: “allotted a neighboring power.” sortita modifies multa, perfect active participle of the deponent verb sortior, “to receive by lot,” “obtain,” with vincinam potentiam its direct object.

obscura: predicate adjective, emphasized by its position.

quod magis mireris: “(something) which may surprise you more”

et implent et effugiunt: the paradoxical nature of the divine, which is somehow all around us, yet flees our sense perception.

sive ... sive: “whether... or… ”

tanta ... quantam: correlatives: “it has subtlety so great that human eyesight cannot perceive it.”

in sanctiore secessu: “in a seclusion too holy” to be seen

regnum suum ... se: nature and god are one in the same. Its “kingdom” is actually itself; god is the natural world and all of its workings.

nec ulli ... nisi animo: only the animus is able to understand the divine, as will be shown in 1.pr.7 (see Selection 10).

quid sit hoc: indirect question after non possumus scire (AG 574): “what this is, without which nothing exists, we cannot know.”

quos igniculos: “some little bit of fire,” i.e. comets. The diminutive emphasizes the grandeur of the universe by contrast. quos = aliquos after si.

cum ... lateat: temporal cum-clause (AG 545).

[7.30.5] New animals are constantly being discovered. The natural world will become better and better known in future generations.

There will be more discoveries in future generations—a thought in line with his musing at Ep. 33.11: “the truth is open to all; not yet has it been captured; much of it still has been left for future generations” (patet omnibus veritas; nondum est occupata; multum ex illa etiam futuris relictum est). As with zoology, so the larger idea that no subject is both discovered and perfected at the same time derives from Aristotle and resonates through Greek and Roman thought (Arist. Poet. 1449a7–15, Cic. Brut. 71.1).

cognovimus: “we have learned about,” true perfect tense.

hoc ... saeculo: ablative of time (AG 423).

multa [negotia]: the word negotia is found in the manuscripts but should be deleted as a marginal intrusion. Supply animalia instead from the preceding clause.

ne hoc quidem: the thought is compressed. (multa) ne hoc quidem (saeculo cognovimus). ne … quidem surrounds and emphasizes the word it negates (AG 322.f).

exoleverit: “has passed away” (LS exolesco II.B), future perfect indicative in a temporal cum-clause (AG 547).

nostri: “of us,” the normal form of the objective genitive > nos; for the partitive genitive, nostrum is regularly used (AG 143.c).

pusilla ... habeat: the final sententia plays on two of the meanings of mundus. The first instance should be translated as “universe” or “world,” but the second “generation.” omnis mundus is the subject of quaerat in a relative clause of purpose (AG 531). The phrasing also recalls the conclusion of the previous book, where Seneca writes about death and the soul: “the soul of man is a tiny thing, but contempt for the soul is a huge thing” (pusilla res est hominis anima, sed ingens res contemptus animae, NQ 6.32.4).

[7.30.6] The sacred mysteries of nature are not revealed all at once; some we will see, others will await future generations.

The comparison of the mysteries of science to the hidden sacred objects used in initiatory cults like that at Eleusis suggests that Seneca believes the comfort and security that was said to be given to initiates of such cults will also be imparted to those who understand the secrets of nature and read his Naturales Quaestiones. The therapeutic nature of all the Hellenistic schools has been stressed by numerous scholars (see Sellars 2018: 9–10 for an overview).

non ... traduntur: “certain sacred rites are not revealed once and for all.” See LS trado II.B.3, “to deliver by teaching”).

Eleusin: the sanctuary at Eleusis near Athens was home to the Eleusinian Mysteries. This elaborate ceremony took place annually and involved a public procession and a private initiation. Typically, individuals would be initiated (mysteria = “secret rites,” mystes = “one being initiated”) usually once in a lifetime. Within the Telesterion (“Great Hall”) there was an inner chamber where certain sacra (“sacred objects”) were kept. The secret initiation seems to have promised spiritual comfort and a blessed existence after death for its initiates. Some sort of sacra were revealed during the ceremonies, but their exact nature is still unclear.

servat: “keeps back,” “reserves”

revisentibus: “to those being initiated a second time,” evidently a rarity in this cult.

initiatos nos credimus?: supply esse. The questioning tone shows how far we still have to go to achieve true knowledge.

arcana: the “secrets” of nature (as at Cons. Marc. 25.2)

aliud ... aliud: “one ... another”

quae post nos subibit: supply aetas as an antecedent for quae.

vocabulary

dissimilis dissimile: dissimilar

rubeō rubēre rubuī: to grow red, blush

palleō –ēre –uī: to fade, be pale

līvidus –a –um: livid, slate-colored

āter atra atrum: black

cōnspectus conspectūs m.: sight, view, aspect, look

exclūdō exclūdere exclūsī exclūsus: to shut out/off, remove, exclude, hinder, prevent

dissimilis dissimile: dissimilar 7.27.2

aliquātenus: up to a point, while

dīvertō –ere –vertī –versus: to turn one’s self

comētēs –ae m.: comet

etiamsī: even if, although

porrō: in turn, further, next 7.27.3

cōnsīderō cōnsīderāre: to look closely, examine, consider

dīversus -a -m: different, opposite, contrary, conflicting

Leō –ōnis m.: the constellation Leo

aestus aestūs m.: heat; tide, seething, raging (of the sea)

torreō –ēre –uī tostus: to burn

Aquārius –ī m. : the constellation Aquarius

astringō (adstringō) –stringere –strīnxī –strictum: bind, grasp, tighten, freeze

gelus –ūs m.: frost, cold, ice

effectus –ūs m.: effect, result; with sine = without a decisive result

dissimilis dissimile: dissimilar

Ariēs –etis m.: the constellation Aries

extollō –ere: lift, raise up

Lībra –ae f.: the contellation Libra

ēmergō –gere –sī –sum: to raise, emerge

exiguus –a –um: small, puny, paltry

prōferō prōferre prōtulī prōlātus: bring forward, advance, discover

contrārius –a –um: opposite 7.27.4

elementum –ī n.: an element

frīgidus –a –um: cool, cold

calidus –a –um: warm, hot

ūmidus –a –um: moist, damp

siccus –a –um: dry

concordia concordiae f.: agreement, harmony

discors discordis: disagreeing

comētēs –ae m.: comet

exemplar exemplāris n.: likeness, model, exemplar, image

trīcēsimus –a –um: 30th

revīsō –ere: to revisit, come and see again

varietās varietātis f.: variety 7.27.5

iactō iactāre iactāvī iactātus: to boast (with se)

vēlōx –ōcis: fast

temperō temperāre temperāvī temperātus: to moderate

cōnspicuus –a –um: in view, visible

grex gregis m.: flock, herd, crowd

īgnōrō īgnōrāre īgnōrāvī īgnōrātus: be unfamiliar with, be ignorant of

potentia potentiae f.: power

aliquandō: sometimes

liceō licēre licuī: to be permitted

comētēs –ae m.: comet 7.27.6

attribuō attribuere attribuī attribūtus: to assign

dissimilis dissimile: dissimilar

mōtus mōtūs m.: movement, earthquake (esp with terrae), motion

fōrmōsus (fōrmonsus) –a –um: handsome, beautiful

fortuītus –a –um: accidental, random, haphazard

amplitūdō –inis f.: greatness, extent, size, width, breadth

cōnsīderō cōnsīderāre: to look closely, examine, consider

fulgor –ōris m. or fulgur –ūris n.: lightning, flash, brightness

īnsīgnis īnsīgne: (adj.) remarkable, noted, extraordinary

singulāris singulāris singulāre: singluar, remarkable

angustus –a –um: narrow, close, constrained

coniciō –icere –iēcī –iectus: to throw/pile/put together

artō –āre: fit in; restrict, cramp; cut short

amplector amplectī amplexus sum: to surround, enclose, embrace

Aristotelēs –is or –ī m.: Aristotle 7.28.1

comētēs –ae m.: comet

significō significāre significāvī significātus: show, express, make known, indicate, portend

intemperantia –ae f.: excess

imber imbris m.: rain

dēnūntiō dēnūntiāre dēnūntiāvī dēnūntiātus: to announce, declare, summon

futūrus –a –um: about to be; future

pluvia –ae (sc. aqua) f.: rain, rain shower

scintillō scintillāre: to sparkle, glitter, glow

oleum –ī n.: oil

putrēscō –ere –truī —: rot, putrefy

concrēscō –ere –crēvī –crētus: to harden, condense, congeal

fungus –ī m.: mushroom; lamp-black on a wick

indicium indici(ī) n.: information, evidence

saeviō saevīre saeviī saevitum: to rage, rave, act violent

marīnus –a –um: of the sea

siccus –a –um: dry

lūdō lūdere lūsī lūsus: to play; play with

fulica –ae f.: water-fowl, the coot

palūs –ūdis f.: swamp, marsh, bog

volō volāre volāvī volātus: to fly

ardea –ae f.: the heron

nūbēs nūbis f.: cloud, mist

aequinoctium –ī n.: the equinox

calor –ōris m.: warmth

frīgus frīgoris n.: cold, chill

flectō flectere flēxī flexus: to bend

Chaldaeus –a –um: Chaldaean (soothsayer)

trīste: sadly

comētēs –ae m.: comet 7.28.2

pluvia –ae (sc. aqua) f.: rain, rain shower

minor minārī minātus sum: to threaten

Aristotelēs –is or –ī m.: Aristotle

suspectus –a –um: suspicious

proximus –a –um: neighboring, nearby

repōnō repōnere reposuī repositus: to put back, store

comprehendō (comprendō) comprehendere comprehendī comprehensus: bind together, detect, capture, comprehend

comētēs –ae m.: comet

Paterculus –ī m.: Paterculus (name) 7.28.3

Vopiscus –ī m.: Vopiscus (name)

Aristotelēs –is or –ī m.: Aristotle

Theophrastus –ī m.: Theophrastus (name)

praedicō praedicāre praedicāvī praedicātus: to announce, state

māximus –a –um: greatest; maxime: most, especially, very much

continuus –a –um: connected

ubīque: everywhere

Achaia (Achāïa) –ae f.: Achaia, Roman province taking up the north part of Peloponnesus

Macedonia –ae f.: Macedonia

mōtus mōtūs m.: movement, earthquake (esp with terrae), motion

prōruō –ruere –ruī –rutum: to overthrow, demolish

tarditās –ātis f.: slowness of movement/action 7.29.1

argūmentum –ī n.: proof, evidence, argument

multum: much, a lot

terrēnus –a –um: earthly, terrestrial, land, earth

compellō compellere compulī compulsus: to drive

cardō –inis m.: pivot, turning point, axis, pole

Sāturnus –ī m.: Saturn

lentus –a –um: slow, sluggish

atquī or atquīn: nevertheless; indeed

lēvitās –ātis f.: smoothness

argūmentum –ī n.: proof, evidence, argument

ambitus –ūs m.: revolution, winding, circumference; canvassing for office, bribery, parade, vanity, bombast 7.29.2

circumeo (circueō ) –īre –iī/–īvī circuitus: to travel around, inspect

succurrō –currere –currī –cursūrum: to run up from below, help, assist

comētēs –ae m.: comet

etiamsī: even if, although

sēgnis sēgne: slow

mendācium –ī n.: lie, falsehood

sex; sextus –a –um: 6; 6th

mēnsis mēnsis m.: month

dīmidium dīmidiī n.: half

trānscurrō –ere –currī (–cucurrī) –cursus: to run across; flash or shoot across

proximus –a –um: neighboring, nearby

mēnsis mēnsis m.: month

circumferō –ferre –tulī –lātus: to bear round; pass around 7.29.3

proximus –a –um: neighboring, nearby

septentriōnes –um m.: the north

mōtus mōtūs m.: movement, earthquake (esp with terrae), motion

occidō occidere occidī occāsus: to go down; set; fall

merīdiānus –a –um: of midday, noon; southern

ērigō ērigere ērēxī ērēctus: to raise, rise, set up, excite, encourage

oblitēscō –litēscere –lituī —: to hide/conceal oneself

Claudiānus (Clōdiānus) –a –um: of the gens Claudia, Claudian

septentriōnes –um m.: the north

assiduus –a –um: established, steady

celsus –a –um: high, lofty

excēdō excēdere excessī excessus: to go out/away

comētēs –ae m.: comet

rīmor –ārī –ātus sum: to lay open, cleave, probe, to search

coniectūra –ae f. : conjecture, inference, conclusion, guess

occultus –a –um: hidden, concealed, secret

liceō licēre licuī: to be permitted

fīdūcia fīdūciae f.: trust, confidence, faith.

Aristotelēs –is or –ī m.: Aristotle 7.30.1

verēcundus –a –um: modest

sacrificium sacrifici(ī) n.: sacrifice, offering to a god

sumittō (submittō) –mittere –mīsī –missum: to submit, to lower

toga togae f.: toga

argūmentum –ī n.: proof, evidence, argument

modestia –ae f.: moderation

quantō: by how much, by as much as, according as

disputō disputāre disputāvī disputātus: to discuss, debate, argue.

temerē: rashly

imprūdēns –entis: not seeing or knowing beforehand

īgnōrō īgnōrāre īgnōrāvī īgnōrātus: be unfamiliar with, be ignorant of

affirmō affirmāre affirmāvī affirmātus: to affirm, assert

mentior mentīrī mentītus: to deceive, lie, fabricate

ēruō ēruere ēruī ērutus: to tear out, dig up, bring to light 7.30.2

Panaetius –(i)ī m.: Panaetius, a Stoic philosopher

comētēs –ae m.: comet

ōrdinārius –a –um: regular, normal

dīligēns –ntis: careful

tractō tractāre tractāvī tractātus: to take in hand, handle, investigate, discuss

ēdō ēdere ēdidī ēditum: to issue, produce

comētēs –ae m.: comet

idōneus –a –um: suitable, fit, appropriate

quācumque: wherever, wheresoever

concipiō concipere concēpī conceptum: conceive, catch, draw

ūniversus –a –um: all together, whole, entire

fortuītus –a –um: accidental, random, haphazard

intexō –ere –uī –tus: to weave

occultus –a –um: hidden, concealed, secret

sēcrētum –ī n.: hidden, secret 7.30.3

quotus –a –um: how small (with pars)

tractō tractāre tractāvī tractātus: to take in hand, handle, investigate, discuss

fundō fundāre fundāvī fundātus: to lay the foundation, found, establish, fix

maior māius: bigger

melior melius: better

effugiō effugere effūgī: flee from, escape the notice of, escape

cōgitātiō cōgitātiōnis f.: contemplation, thought, reflection

vīsō vīsere vīsī vīsus: to look at

cognātus –a –um: near by birth 7.30.4

summus –a –um: highest

vīcīna –ae f.: neighbor

sortiō sortīre sortīvī sortītum: to recieve by lot, obtain

potentia potentiae f.: power

obscūrus –a –um: dark, secret, obscure

fortasse: perhaps

effugiō effugere effūgī: flee from, escape the notice of, escape

subtīlitās subtīlitātis f. : subtlety

sanciō sancīre sānxī sānctus: to consecrate

sēcessus –ūs m.: retreat, isolated spot

māiestās –ātis f.: greatness; majesty

dēlitēscō –ere dēlituī: to conceal oneself, lie hidden, lurk

aditus aditūs m.: an approach; entryway

igniculus –ī m.: small fire, spark

māximus –a –um: greatest; maxime: most, especially, very much

animālis –e: aerial; animate 7.30.5

nē…quidem: not even

īgnōtus –a –um: unknown

futūrus –a –um: about to be; future

exoleō –ere — —: to wither

reservō reservāre reservāvī reservātus: to reserve, hold back

pusillus –a –um: very little, petty, insignificant

Eleusīs –īnis f. (acc. –sīn): Eleusis, a religious sanctuary in Greece, home to the Eleusinian Mysteries 7.30.6

revīsō –ere: to revisit, come and see again

initiō initiāre initiāvī initiātus: to initiate

vestibulum –ī n.: forecourt, vestibule

haereō haerēre haesī haesus: cling, be attached to (+dat.); be in doubt; linger, stay

arcānus –a –um: secret, mysterious, hidden

prōmiscu(u)s –a –um: mixed, indiscriminate

redūcō redūcere redūxī reductus: to bring back

interior –ius: inner, secret, deeper