Nepos, Life of Hannibal — Chapter 4: The Battle of Cannae & Its Legacy

"There was no longer any Roman camp, any general, any single soldier in existence."

— Livy, Ab urbe condita 22.54

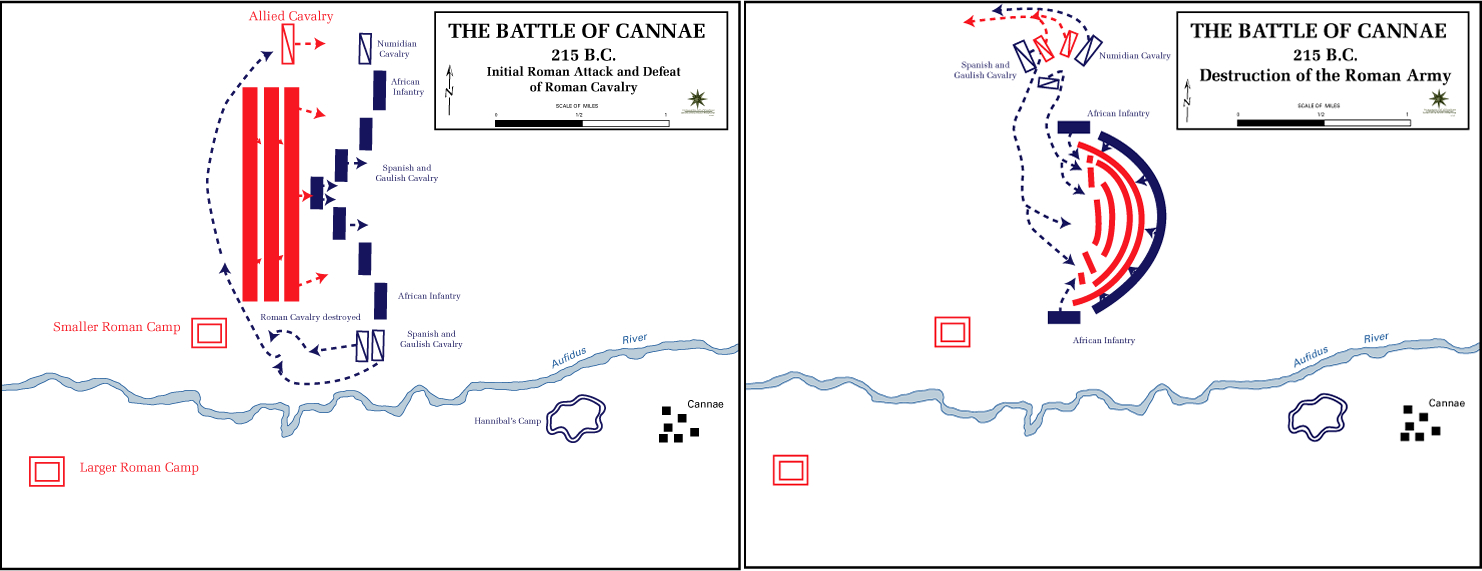

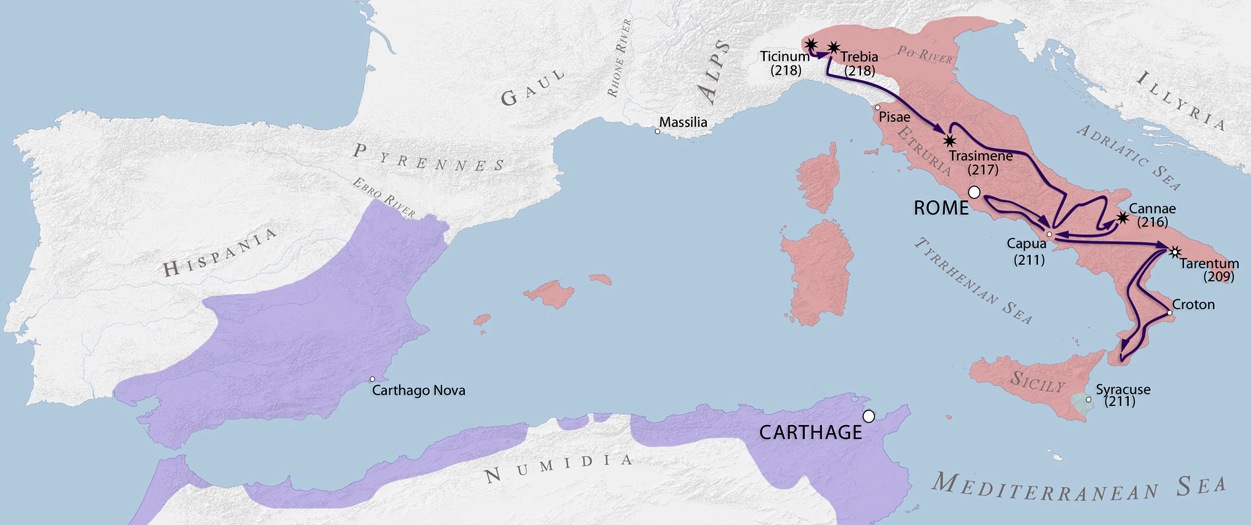

On August 2, 216 BC Rome suffered one of the most catastrophic defeats in military history. The town of Cannae, located about 300 miles south of Rome in Apulia, controlled the approaches to southern Italy and operated a granary important for supplying food to the city of Rome. There, on a flat, featureless plain, Hannibal accomplished a feat that was thought to be impossible: with his small army he enveloped a much larger Roman force. Surrounded and unable to maneuver, the Roman army disintegrated as a coherent fighting force.

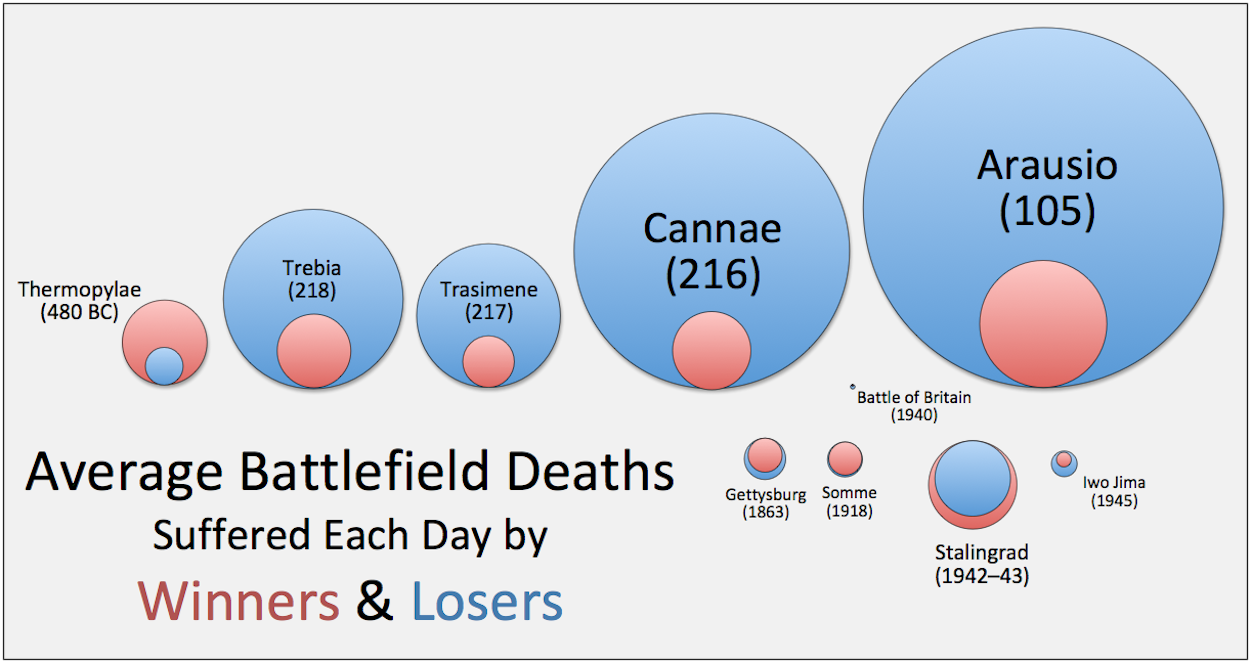

According to Livy, 48,200 Romans were killed and another 20,000 captured before nightfall put a stop to the slaughter. Polybius puts the number of dead at 70,000. The victory had been costly for Hannibal as well. Nearly 6,000 of his troops fell in the battle. Modern historians tend to be more conservative about the size of the Roman army, but even so they put the number of Roman dead at around 30,000. Regardless of the exact toll, the greatest army that Rome had fielded to that point—a grand army assembled with the sole purpose of driving Hannibal out of Italy—had been annihilated. The consul Aemilius Paullus lay among the dead, as did both consular quaestors, 29 military tribunes, and another 80 men of senatorial rank. According to Livy, the surviving consul, Terentius Varro, escaped from Cannae with a mere fifty soldiers. The Roman defeat was total.

The scale of the slaughter at Cannae is difficult to comprehend. If the ancient estimates of casualties are accurate, Cannae saw the second deadliest single day of combat ever visited on a western army, and it is estimated that over one hundred Romans died every minute during the height of the battle. Regardless of the exact number of dead, there is no disputing the magnitude of the disaster that Hannibal had inflicted upon Rome, or the daring and brilliance he and his troops displayed on that day.

Hannibal’s tactics at Cannae are often regarded as the most effective large-scale battle maneuvers in history, setting the standard by which military commanders continue to measure their success. Count Alfred von Schlieffen, the architect of Germany’s strategy in World War I, believed that victory was possible for Germany provided that they followed Hannibal’s example. As Dwight D. Eisenhower observed, "every ground commander seeks the battle of annihilation; so far as conditions permit, he tries to duplicate in modern war the classic example of Cannae."1

In the successive battles of Trebia, Trasimene, and Cannae, Hannibal had destroyed the equivalent of eight consular armies. In only 20 months he had killed as many as 150,000 men, or, by some estimates, one-fifth of all adult men in Rome and its allied cities. By way of comparison, that is three times the number of dead the (much more populous) United States lost in Vietnam, and thirty times the number lost in battle during the decade after 9/11. Even as Rome attempted to cope with these disasters, another befell them when the Gauls destroyed an army of 25,000 Romans near Litana in northern Italy.

In response to this unprecedented carnage, Rome's empire began to fracture. Capua, the second largest city in Italy, defected to Hannibal, as did several important cities in Apulia, Lucania, and Bruttium. Most troubling for the Romans, the 12 Latin cities, Rome’s oldest and closest allies, declined to supply troops for the new army. Their mood was not placated when a proposal to enroll two senators from each Latin city into the depleted Senate was vehemently rejected (one senator even threatened to kill on sight any Latin who dared appear in the Senate). With Rome’s alliances unraveling, Hannibal seemed poised for victory. At home, the treasury was bare and Rome resorted to loans to pay its troops. International opinion began to flow towards Hannibal and in 215 he signed an alliance with Philip V of Macedon. In Sicily, Hiero of Syracuse, a stalwart ally of Rome (and source of troops, money, and grain) died and his grandson, Hieronymus, quickly shifted his support to Carthage.

Yet Rome still refused to surrender. The Romans appointed another dictator, Marcus Junius Pera, to organize the defense of Rome and begin levying new troops. Within a month of the disaster at Cannae, Rome could field four legions, even if these were composed of freed slaves and convicts. To divine the cause of the gods' displeasure they dispatched an envoy to consult the oracle at Delphi and to placate the gods they ordered the sacrifice of two Gauls and two Greeks. Hannibal, unable to besiege Rome because of his limited manpower and his need to provision his troops, bypassed the city and marched towards his new allies in Campania.

Hannibal’s decision to bypass Rome after his victory at Cannae fostered one of the great military debates in antiquity. According to legend, after the battle the commander of Hannibal's cavalry suggested that Hannibal would be dining in victory on the Capitoline Hill within five days if he only had the courage to strike at the city. Centuries later, young Roman students were still assigned to debate his decision, as the Roman satirist Juvenal (ca. late first century AD) recalls:

|

1.Eisenhower, D. 1948. Crusade in Europe, 325. |