By Kyle Gervais

Classical Latin poetry uses quantitative meters: lines of verse with particular patterns of long and short syllables. This can be distinguished from the accentual meters used in English poetry (and in a lot of medieval Latin poetry), where lines of verse have particular patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables; we can think of the alternating stressed and unstressed syllables in Shakespeare’s “A hórse! A hórse! My kíngdom fór a hórse!” (Richard III, Act V, Scene 4) or the Fresh Prince’s “In wést Philadélphia bórn and raísed.”

To recognize the patterns of long and short syllables in quantitative meters, you need to know the rules that determine the length of a Latin syllable in poetry and prose, as well as rules specific to Latin poetry such as the elision of syllables. For the basics of this topic, we refer readers to the excellent introduction to scansion in William Turpin’s DCC edition of Ovid, Amores 1 (but note that the section on “the elegiac couplet” is not relevant to Seneca).

Seneca uses different meters for the acts and the choral odes in his plays. While it is probably more important for you to be comfortable with the meter of acts, since these constitute the bulk of the play, this meter is more complicated to learn than the meters in the choral odes. We will therefore begin with the odes.

The odes: lyric meters

As in Greek tragedy, Seneca writes his choral odes in a variety of lyric meters (meters used especially for lyric poetry as opposed to, say, epic poetry). But unlike the often complicated and shifting lyric meters in Greek tragedy, Seneca typically uses only one or two fairly straightforward meters for each ode. Odes 2 and 3 have metrical patterns which do not vary at all from line to line; the meter used in odes 1 and 4 is a bit more complicated because certain variations are allowed.

Ode 2: Lesser Asclepiad

Every line in Ode 2 is a “lesser Asclepiad” (named after the Greek lyric poet Asclepiades of Samos and called “lesser” to distinguish it from a longer “greater Asclepiad” line). The pattern of twelve long and short syllables is always as follows:

– – – u u – || – u u – u x

Symbol key:

- – indicates a long syllable

- u indicates a short syllable

- x indicates a anceps syllable that can be either long or short (an anceps is always found at the end of the line)

- || indicates a caesura (see below)

We can break up this long line into shorter, more manageable segments by noting two features.

- Every line is divided in the middle by a “caesura” (indicated by the symbol ||). This break between words always occurs between the sixth and seventh syllable.

- The line features two “choriambs”: the metrical pattern – u u – . These choriambs occur right before and after the caesura. This metrical foot is very common in lyric meters and will appear in the next 2 meters we discuss.

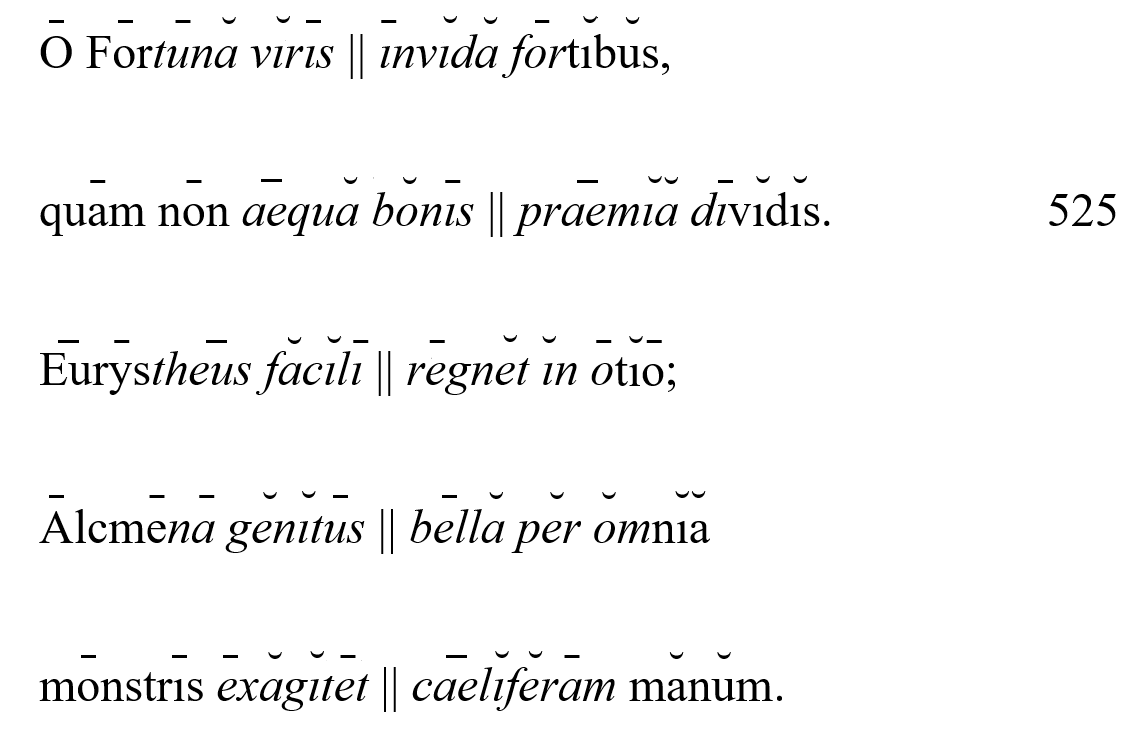

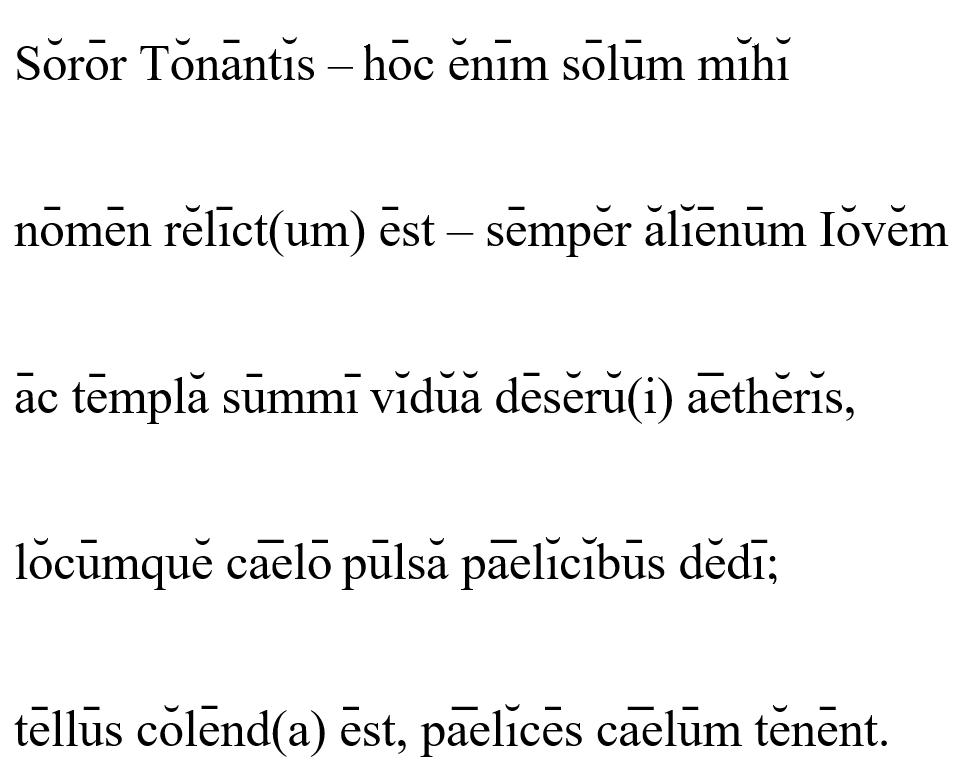

Here are the first five lines of ode 2 scanned, with syllable lengths and caesuras indicated, and choriambs italicized:

Ode 3: Sapphic and glyconic

In ode 3, lines 830–74 are written in Sapphics (named after the famous lyric poet Sappho). The lines can also be called Sapphic hendecasyllables (a Greek word referring to the 11 syllables of the line). The pattern is as follows:

– u – – – || u u – u – x

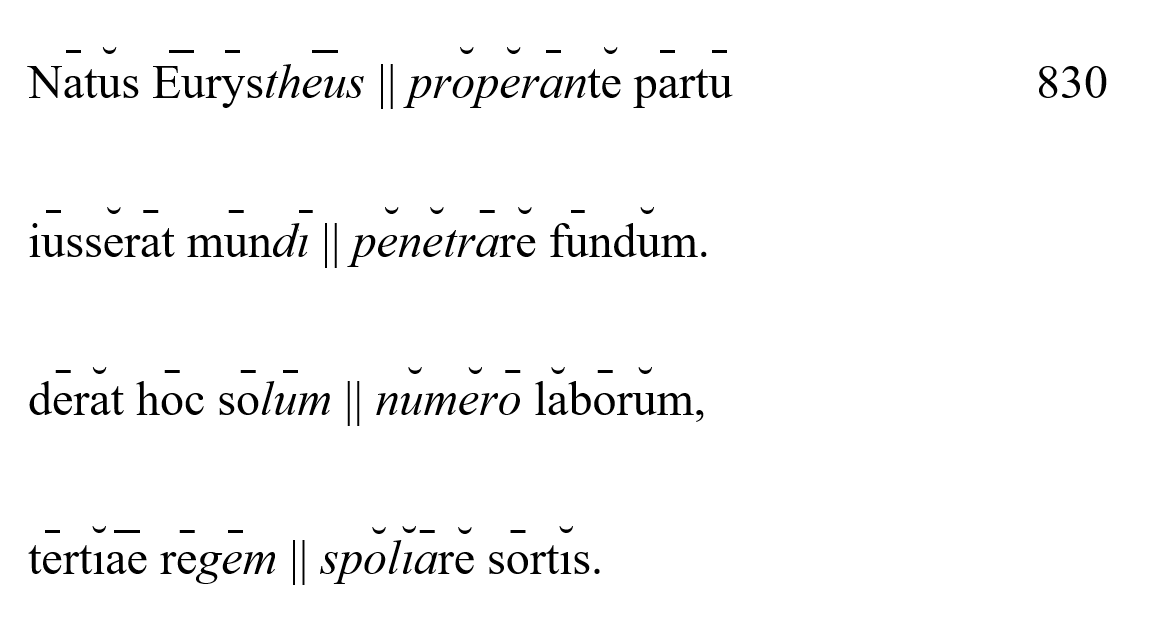

Once again, we can note the choriamb and the mid-line caesura. In this meter, the caesura is after the fifth syllable (which is also the first syllable of the choriamb). Here are the first four lines of the ode scanned:

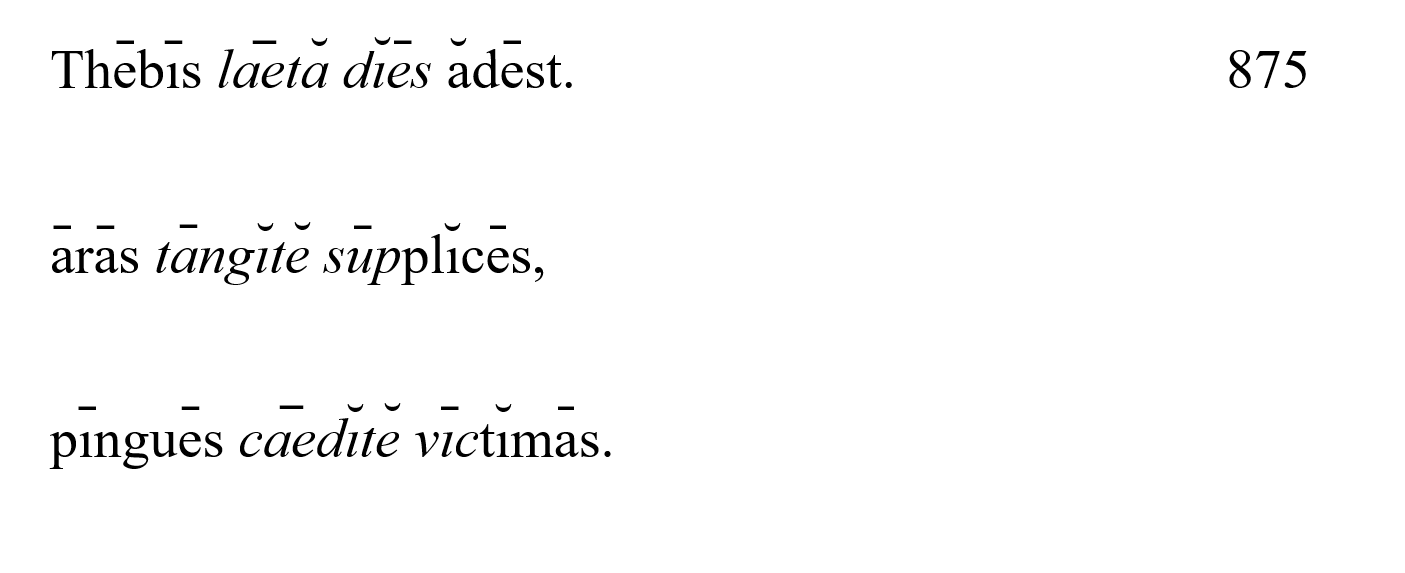

Lines 875-94 are written in shorter lines called glyconics. These lines are also built around a choriamb, but do not have a caesura:

– – – u u – u x

Here are the first three glyconics of the ode:

Odes 1 and 4: anapestic dimeter and monometer

The first and last odes use a meter based on a foot called the anapest: u u –. Two anapestic feet make an anapestic “metron” (plural: “metra”). Most lines in the odes are dimeters: two anapestic metra (four anapests in total). Seneca regularly inserts a caesura in the middle of the line, between the two metra. The basic pattern is therefore as follows:

u u – u u – || u u – u u –

Seneca also occasionally writes a monometer (one anapestic metron, two anapests in total):

u u – u u –

A long syllable takes about the same time to pronounce as two shorts syllables. Therefore, variations on the basic anapestic pattern are created by substituting one long syllable for two short syllables, or two shorts for one long. These substitutions can transform an anapest into a dactyl (– u u) or spondee (– –); tetrabrachs (u u u u) are not used by Seneca. Thus, an anapestic dimeter has the following possible patterns:

|

1a |

1b |

2a |

2b |

|

u u – |

u u – |

u u – |

u u – |

|

– – |

– – |

– – |

– – |

|

– u u |

|

– u u |

|

(Note that a dactyl almost never appears in positions 1b or 2b.)

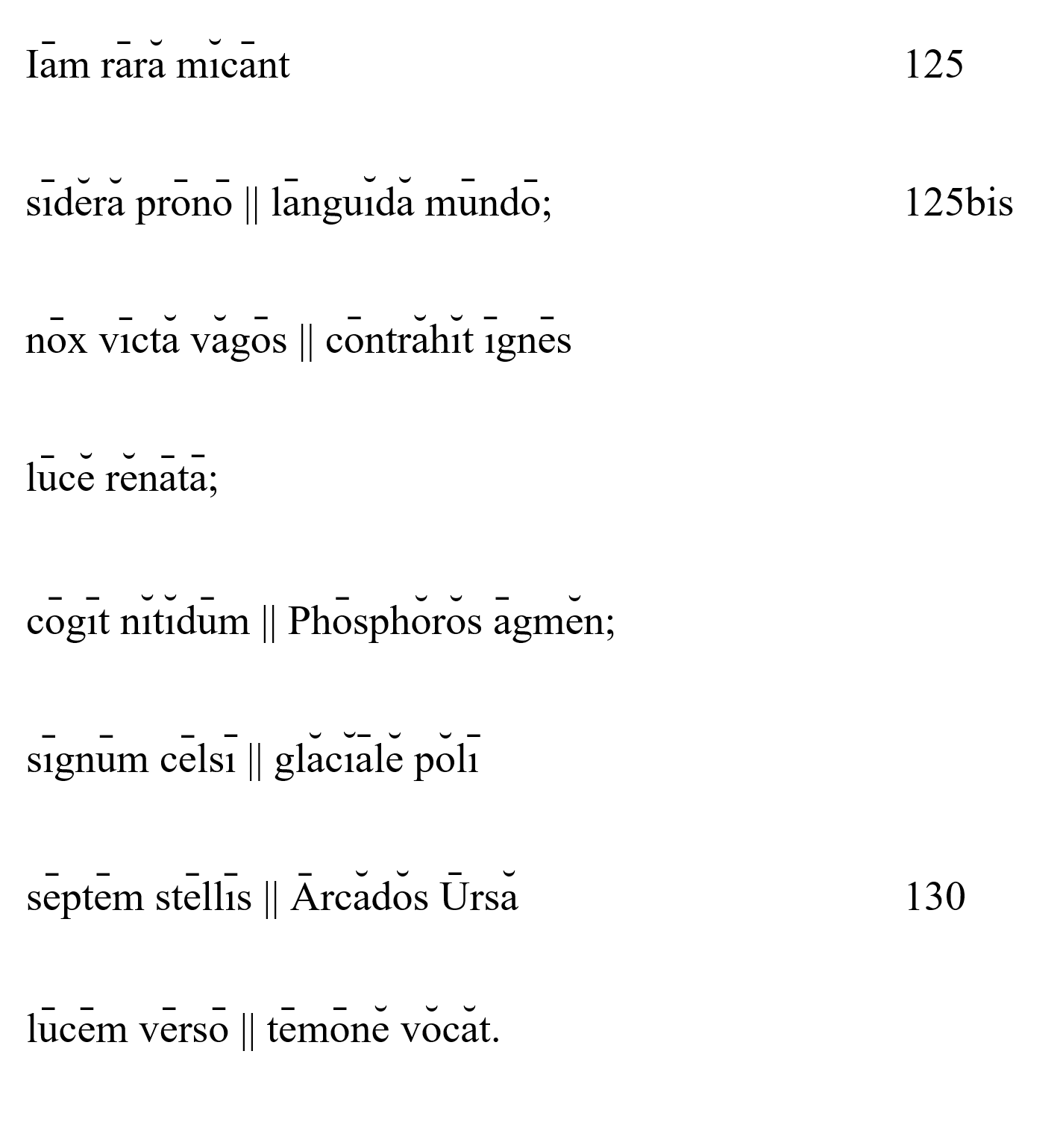

In fact, although this meter is called “anapestic,” dactyls and spondees appear more frequently than anapests. For instance, here are the first eight lines of ode 1:

|

|

1a |

1b |

2a |

2b |

|

125 (monometer) |

– – |

u u – |

|

|

|

125bis |

– u u |

– – |

– u u |

– – |

|

126 |

– – |

u u – |

– u u |

– – |

|

127 |

– u u |

– – |

|

|

|

128 |

– – |

u u – |

– u u |

– – |

|

129 |

– – |

– – |

u u – |

u u – |

|

130 |

– – |

– – |

– u u |

– – |

|

131 |

– – |

– – |

– – |

u u – |

The acts: iambic trimeter

The meter used in the acts of Seneca’s tragedies is called iambic trimeter. This meter is also used in Greek tragedy (in a slightly different form). The basic unit is an iamb (u –). An iambic metron consists of two iambic feet. Each line of iambic trimeter has three iambic metra, for a total of six iambs. So the basic pattern of the line is as follows:

|

1a |

1b |

2a |

2b |

3a |

3b |

4a |

4b |

5a |

5b |

6a |

6b |

|

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

x |

Certain variations are allowed in this basic pattern. By far the most common variation is that in the first, third, and fifth iamb, the initial short syllable can be replaced by a long syllable, creating a spondee (– – ). In fact, the fifth foot is almost never an iamb. So we can represent the metrical pattern more accurately as follows:

|

1a |

1b |

2a |

2b |

3a |

3b |

4a |

4b |

5a |

5b |

6a |

6b |

|

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

– |

– |

u |

x |

|

– |

|

|

|

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Furthermore, most long syllables can be replaced by two short syllables. By introducing these two short syllables, we can produce not only iambs and spondees, but also dactyls (– u u), anapests (u u –), tribrachs (u u u), and tetrabrachs (u u u u). We can thus see the full range of possibilities in this meter:

|

1a |

1b |

2a |

2b |

3a |

3b |

4a |

4b |

5a |

5b |

6a |

6b |

|

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

– |

– |

u |

x |

|

– |

|

|

|

– |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

uu |

uu |

|

uu |

uu |

uu |

|

uu |

uu |

|

|

|

This is clearly a lot of possible variation. We can see some of the different patterns at work in the opening lines of the play. In these lines, the variation happens to be towards the end of verses:

|

Line |

1a |

1b |

2a |

2b |

3a |

3b |

4a |

4b |

5a |

5b |

6a |

6b |

|

1 |

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

u |

– |

– |

– |

u |

x |

|

2 |

– |

– |

u |

– |

– |

– |

u |

uu |

– |

– |

u |

x |

|

3 |

– |

– |

u |

– |

– |

uu |

u |

– |

uu |

– |

u |

x |

|

4 |

u |

– |

u |

– |

– |

– |

u |

– |

uu |

– |

u |

x |

|

5 |

– |

– |

u |

– |

– |

– |

u |

– |

– |

– |

u |

x |

It can be helpful to notice some things that do not vary in this meter. Positions 2a and 4a always contain one short syllable. Furthermore, the verse almost always ends with the pattern – – u x or uu - u x (in positions 5a to 6b).

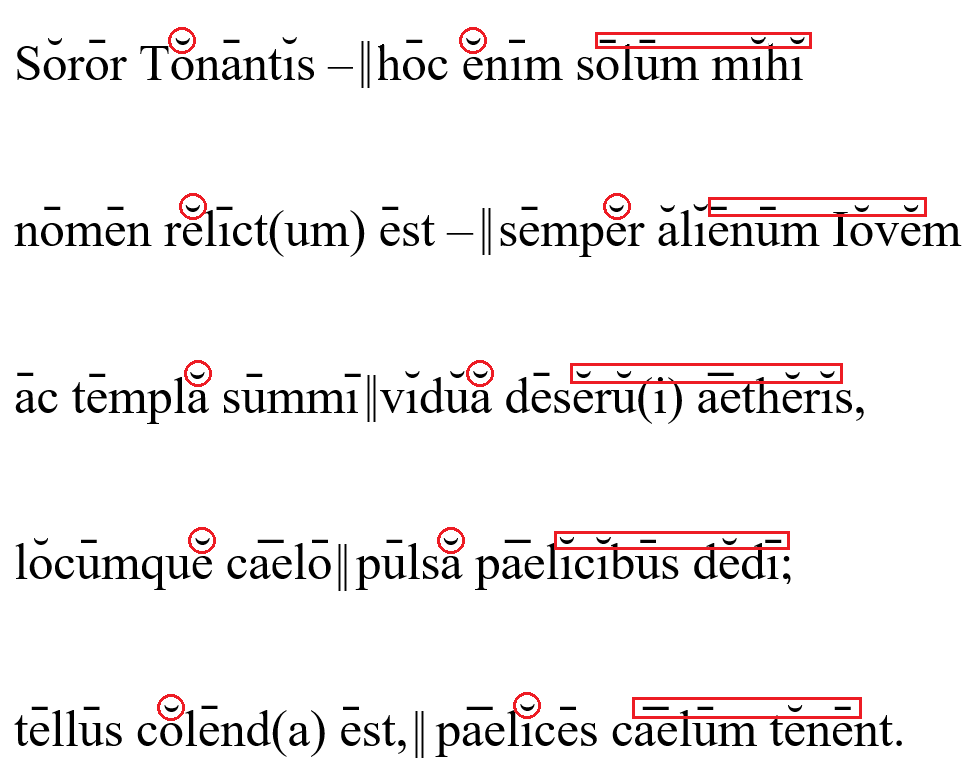

Another helpful feature to notice is that lines of iambic trimeter are divided near the middle by a caesura. In Seneca, this caesura is almost always in the 3rd foot, right after the 3a position. This can be seen in the first five lines (the caesura is indicated by the symbol || and the 2a, 4a, and 5a-6b positions are circled):

Learning to look for a word division in the 3rd foot can help to break up the longer lines into two more manageable parts. Significantly, there is often (though not always) a sense break that coincides with the caesura: i.e., you will often notice a punctuation mark at this position in the line (as in lines 1, 2, and 5 above).

Learning Latin meter can be difficult at first, and you will probably find yourself getting lost in the middle of many lines. Take your time marking each syllable as long or short and finding the caesura. Once you have a line correct, read it out loud a few times, exaggerating the rhythm. With enough practice, you may be able to “hear” the rhythm of Seneca’s iambic trimeters and lyric meters. If you can reach this point, you will have come closer to fully appreciating the music that makes Seneca’s plays beautiful poetry, and not simply prose.

Performance Styles

To help you begin to hear Seneca’s poetic music, this commentary includes readings of various passages by a host of talented volunteers, both instructors and students. Whether you’re reciting the Latin for others, reading it aloud to yourself, or even hearing it in your head, every reading of Seneca’s poetry is a performance, in which the performer chooses different aspects of the text to explore and emphasize. You’ll find that some of our readers have allowed you to clearly hear Seneca’s meter. Others have chosen to highlight the conversational aspect of Seneca’s dialogue, letting their performance be guided by the rhythms of the characters’ thoughts. Still others have embraced the drama of the play, navigating the shifting emotions of Seneca’s ill-fated characters. All of these approaches bring out essential aspects of Hercules Furens. We encourage you to explore some of this in your own performances.