Iamque ībat dictō pārēns et dōna Cupīdō695

rēgia portābat Tyriīs duce laetus Achātē.

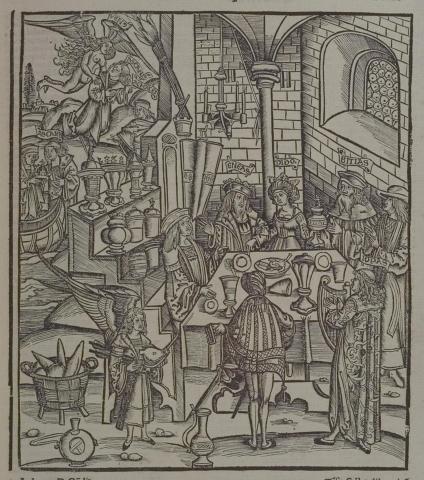

Cum venit, aulaeīs iam sē rēgīna superbīs

aureā composuit spondā mediamque locāvit,

iam pater Aenēās et iam Trōiāna iuventūs

conveniunt, strātōque super discumbitur ostrō.700

Dant manibus famulī lymphās Cereremque canistrīs

expediunt tōnsīsque ferunt mantēlia villīs.

Quīnquāgintā intus famulae, quibus ōrdine longam

cūra penum struere et flammīs adolēre Penātēs;

centum aliae totidemque parēs aetāte ministrī,705

quī dapibus mēnsās onerent et pōcula pōnant.

Nec nōn et Tyriī per līmina laeta frequentēs

convēnēre; torīs iussī discumbere pictīs

Mīrantur dōna Aenēae, mīrantur Iǖlum,

flagrantēsque deī vultūs simulātaque verba,710

pallamque et pictum croceō vēlāmen acanthō.

Praecipuē īnfēlīx, pestī dēvōta futūrae,

explērī mentem nequit ārdēscitque tuendō

Phoenissa, et pariter puerō dōnīsque movētur.

Ille ubi complexū Aenēae collōque pependit715

et magnum falsī implēvit genitōris amōrem,

rēgīnam petit. Haec oculīs, haec pectore tōtō

haeret et interdum gremiō fovet īnscia Dīdō

īnsīdat quantus miserae deus. At memor ille

mātris Acīdaliae paulātim abolēre Sychaeum720

incipit et vīvō temptat praevertere amōre

iam prīdem residēs animōs dēsuētaque corda.

notes

Cupid, having thus entered the palace, disguised as the child Ascanius, exercises his power over the mind of the queen, to make her forget Sychaeus and love Aeneas. (F-D).

695 ībat: he had been fetched, and was on his way; dicto parens picks up paret Amor dictis (689): Cupid is a conscientious, obedient child, carrying out his instructions to the letter (Austin).

696 duce laetus Achātē: “gladly following Achates”; expressing the joie de vivre of young or strong creatures (Conway).

697 cum venit: “as he approaches”; this use of the historic present after cum and postquam is a poetical and colloquial survival (Conway).

697 aulaeīs: curtains, overhanging the banqueting-couches, either as a canopy or as wall-tapestry (Austin).

698 aureā: is ablative, scanned as a spondee (Conway).

698 compusuit … mediamque locāvit: by the Vergilian idiom, the -que takes the place of postquam. Mediam agrees with se and refers to her place in the whole gathering—certainly not, as some have supposed, to the center of an ordinary triple couch (Conway).

699 pater Aenēās: pater marks Aeneas’ status and responsibilities vis-à-vis the Troiana iuventus, i.e. the men referred to in 510 (Austin).

700 discumbitur: “the company takes its places,” impersonal passive (AG 372).

701 manibus: dative “to pour over the hands”; this is why Vergil put it closely after dant (Conway).

702 mantēlia: “towels for the hands,” as the word (from manus and tela) literally means (Conway).

702 tōnsīs villīs, with the “nap,” i.e. the ends of the thread, closely clipped so as to present a firm but not too rough a surface (Conway).

703 intus: these servants are working behind the scenes, in the kitchen or storerooms.

703 ōrdine: “duly,” in proper sequence of duty (not “in a line,” which would be highly inconvenient for work in the store-room) (Conway).

703-4 longam / ... penum struere: “to arrange and serve the long succession of courses” (Bennett).

704 cūra: supply est.

704 flammīs adolēre Penātēs: “to heap high the hearth with fire,” ornate Vergilian epic style; the task is a solemn one, a ritual to be carefully observed, and therefore Vergil describes it in rich and mysterious terms. The household Penates—the gods of the penus—are put for the hearth, their holy place (Austin).

705 aliae: these wait at the table, as distinct from those intus (703) (Austin).

705 parēs aetāte: “all of the same age,” as compared one with another (not with the women slaves) (Conway).

ministrī: “waiting-men” (Comstock).

706 quī onerent et pōnant: relative clauses of purpose (AG 531.2) (Bennett).

707 Nec nōn et: this connecting formula does not appear before Vergil, and it is not found in prose before the Silver period (Austin).

707 frequentēs: “crowding in” (Conway).

707 līmina: “halls” (Comstock).

708 iussī: placed where it is clearly represents the instructions given to the guests as each arrived by the royal stewards, “to take their several places” (discumbere) (Conway).

710 flagrantēsque … verba: parenthetical statement referring to “Iulus” — that is, Cupid (FC).

713 explērī mentem: probably expleri is “middle,” with mentem a direct object, marking Dido’s own action upon herself: she “cannot have her heart’s fill.”

713 ardescit: continues the fire-metaphor (Austin).

715 ubi: temporal, “when.”

716 falsī genitōris: subjective genitive (AG 343).

716 implēvit: “satisfied” (Conway).

717 petit: “turns upon, attacks,” with definitely hostile intentions (Conway). The strong pause at the second-foot diaeresis is dramatic, and gives great force to the words (Austin).

717: Haec … haec: the pronouns connect the two clauses by anaphora, like mirantur in 709, and point to Dido as the center of the scene, the growth of whose passion is the real event of the banquet—poor inscia Dido as the next line names her (Conway).

718 gremiō fovet: intentionally repeated from 692; Cupid is cuddled as Ascanius was—so the spell of Venus works (Conway).

719 miserae: “to her sorrow,” proleptic: the poet’s own comment; miser is often used of the misery brought by love (Austin).

719 ille: Cupid.

720 abolēre: “to blot out” (Comstock).

720 mātris Acīdaliae: Venus is called from the fountain Acidalia where she often bathes with her attendants (Bennett). Servius connects the rare Acidalia with Greek ἀκίς, "arrow, dart, care, pang." Acidalia thus suggests both curae and the arrows of Cupid. Vergil's mater Acidalia seems to be the "mother who produces sharp curae." (J.J. O'Hara, True Names: Vergil and the Alexandrian Tradition of Etymological Wordplay [Ann Arbor: U. Michigan Press, 2017] p. 129.)

721 praevertere: literally “turn (her heart) first towards.”

721 vīvō amōre: “with living love” (Chase), as opposed to her love for Sychaeus (G-K).

722 iam prīdem … corda: “her long-slumbering soul and unused heart” (Carter).

vocabulary

dictum, ī, n.: a thing said; word, 1.197; command, precept, injunction, 1.695; promise, 8.643. (dīcō)

cupīdō, inis, f.: ardent longing, desire; love, 7.189; ardor, thirst, 9.354; resolve, 2.349; personified, Cupīdō, inis, m., Cupid the son of Venus, and god of love, 1.658. (cupiō)

Tyrius, a, um: adj. (Tyrus), of Tyre; Tyrian or Phoenician, 1.12; subst., Tyrius, iī, m., a Tyrian, 1.574; pl., 1.747.

Achātēs, ae, m.: Achates, a companion of Aeneas, 1.174, et al.

aulaeum, ī, n.: a curtain, covering, hangings, embroidered stuff, tapestry, 1.697.

rēgīna, ae, f.: a queen, 1.9; princess, 1.273. (rēx)

sponda, ae, f.: the frame of a bedstead or couch; a couch, 1.698.

locō, āvī, ātus, 1, a.: to place, put, 1.213, et al.; lay, 1.428; found, 1.247. (locus)

Aenēās, ae, m.: 1. A Trojan chief, son of Venus and Anchises, and hero of the Aeneid, 1.92. 2. Aenēās Silvius, one of the Alban kings, 6.769.

Trōiānus, a, um: adj. (Trōia), Trojan, 1.19; subst., Trōiānus, ī, m., a Trojan, 1.286; pl., Trōiānī, ōrum, m., the Trojans, 5.688.

iuventūs, ūtis, f.: youthfulness; the age of youth; collective, young people, the youth; warriors, 1.467. (iuvenis)

strātum, ī, n.: that which is spread out; a layer, cover; bed, couch, 3.513; pavement, 1.422. (sternō)

discumbō, cubuī, cubitus, 3, n.: to recline separately; recline at table, 1.708; (impers.), discumbitur, they recline, 1.700.

ostrum, ī, n.: the purple fluid of the murex; purple dye, purple, 5.111; purple cloth, covering or drapery, 1.700; purple decoration, 10.722; purple trappings, housings, 7.277.

famulus, ī, m.: pertaining to the house; a house servant or slave; manservant, 1.701; attendant, 5.95.

lympha, ae, f.: clear spring water; water, 4.635, et al.; pl., for sing., 1.701, et al.

Cerēs, eris, f.: daughter of Saturn and Ops, and goddess of agriculture; (meton.), corn, grain, 1.177; bread, 1.701; cake, loaf, 7.113; Cerēs labōrāta, bread, 8.181.

canistra, ōrum, n. pl.: a basket; baskets, 1.701.

expediō, īvī or iī, ītus, 4, a.: to make the foot free; to extricate, disentangle; bring forth, get ready, 1.178; seize, use, 5.209; serve, 1.702; unfold, describe, disclose, 3.379, 460; declare, 11.315; pass. in middle sig., make one’s way out, escape, 2.633. (ex and pēs)

tondeō, totondī, tōnsus, 2, a.: to shear; finish, 1.702; clip, trim, 5.556; browse, feed upon, graze upon.

mantēle, is, n.: a handcloth, a napkin, towel, 1.702.

villus, ī, m.: shaggy hair, 5.352; nap, 1.702.

quīnquāgintā: num. adj. indecl. (quīnque), fifty, 1.703.

intus: (adv.), within, 1.294, et al. (in)

famula, ae, f.: a female house slave; maidservant, 1.703. (famulus)

penus, ūs and ī, m. and f.: food, provisions, the household store of provisions, stores,1.704.

struō, strūxī, strūctus, 3, a.: to place side by side or upon; to pile up; build, erect, 3.84; cover, load, 5.54; arrange, 1.704; like īnstruō, to form or draw out a line of battle, 9.42; (fig.), to plan, purpose, intend, 4.271; bring about, effect, 2.60. (rel. to sternō)

adoleō, oluī, ultus, 2, n.: to light a fire, kindle, 7.71.

Penātēs, ium, m.: gods of the household; hearth-, fireside gods, 2.514, et al.; tutelary gods of the state as a national family, 1.68; (fig.), fireside, hearth, dwelling-house, abode, 1.527. (penus)

totidem: (num. adj. pron., indecl.), just, even so many; as many, 4.183, et al.

minister, trī, m.: a subordinate; an attendant, minister, waiter, servant, 1.705; helper, creature, tool, agent, 2.100. (cf. minus)

daps, dapis, f.: a feast, banquet, 1.210; food, viands, 1.706; flesh of sacrificial victims, 6.225; usually found in the pl., but the gen. pl. is not used.

onerō, āvī, ātus, 1, a.: to load; the thing or material with which, usually in abl. and rarely in acc., 1.706; stow, lade, store away, w. dat. of the thing receiving, 1.195; (fig.), burden, overwhelm, 4.549. (onus)

pōculum, ī, n.: a drinking-cup; goblet, 1.706; draught, drink. (cf. pōtō, drink)

torus, ī, m.: a bed, couch, 1.708; seat, 5.388; royal seat, throne, 8.177; bank, 6.674; the swelling part of flesh; a brawny muscle.

pīctus, a, um: embroidered, 1.708; many-colored, speckled, spotted, variegated, 4.525.

Iūlus, ī, m.: Iulus or Ascanius, son of Aeneas, 1.267, et freq.

flāgrō, āvī, ātus, 1, n.: to be on fire or in flames; burn, blaze, 2.685; glow, 1.710; flash, 12.167; blush, 12.65; rage, 11.225.

simulō, āvī, ātus, 1, a.: to make similar; imitate, 6.591; pretend, 2.17; to make a false show of, feign, 1.209; p., simulātus, a, um, made to imitate, counterfeiting, 4.512; dissembling, 4.105; imitating, resembling, 3.349. (similis)

palla, ae, f.: a long and ample robe; mantle, 1.648.

pingō, pīnxī, pīctus, 3, a.: to paint, 5.663; color, stain, dye, 7.252; tattoo, 4.146.

croceus, a, um: adj. (crocus), of saffron; saffron-colored, yellow, 4.585.

vēlāmen, inis, n.: a veil, 1.649; a covering, garment, vestment, 6.221. (vēlō)

acanthus, ī, m.: the plant bear's-foot; the acanthus, 1.649.

praecipuē: (adv.), chiefly, especially, particularly, most of all, 1.220. (praecipuus)

īnfēlīx, īcis: (adj.), unlucky; unfortunate, luckless, unhappy, 1.475, et al.; sad, miserable, 2.772; of ill omen, ill-starred, ill-boding, fatal, 2.245; unfruitful.

pestis, is, f.: destruction, 5.699; plague, pest, scourge, 3.215; death, 9.328; infection, pollution, 6.737; fatal, baneful passion, 1.712. (perdō)

dēvoveō, vōvī, vōtus, 2, a.: to set apart by vows; devote, 12.234; p., dēvōtus, a, um, devoted, destined, doomed, 1.712.

futūrus, a, um: about to be; future, 4.622. (sum)

expleō, plēvī, plētus, 2, a.: to fill completely; fill up; gorge, 3.630; satisfy, 1.713; finish, complete, 1.270; w. gen., satiate, glut, 2.586.

nequeō, īvī or iī, itus, īre, irreg. n.: to be unable; can not, 1.713.

ārdēscō, ārsī, 3, inc. n.: to begin to burn; (fig.), burn, 1.713; to increase, grow louder and louder, 11.607. (ārdeō)

tueor, tuitus or tūtus sum, 2, dep. a.: to look at, gaze upon, behold, regard, 4.451, et al.; watch, guard, defend, maintain, protect, 1.564, et al.; p., tūtus, a, um, secure, safe; in safety, 1.243; sure, 4.373; subst., tūtum, ī, n., safety, place of safety, 1.391; pl., tūta, ōrum, safe places, safety, security, 11.882; adv., tūtō, with safety, safely, without danger, 11.381.

Phoenissus, a, um: (adj.), Phoenician, 1.670; subst., Phoenissa, ae, f., a Phoenician woman; Dido, 1.714, et al.

pariter: (adv.), equally, 2.729; also, in like manner, in the same manner, on equal terms, 1.572; side by side, 2.205; at the same time, 10.865; pariter — pariter, 8.545. (pār)

complexus, ūs, m.: an embracing; embrace, 1.715. (complector)

collum, ī, n.: the neck of men and animals, 1.654, et al.; of a plant, 9.436; pl., the neck, 11.692.

pendeō, pependī, 2, n.: to hang, foll. by abl. alone or w. prep., 2.546, et al.; 5.511; be suspended, 1.106; cling, 9.562; bend, stoop forward, 5.147; (meton.), linger, delay, 6.151; listen, hang upon, 4.79.

genitor, ōris, m.: he who begets; father, sire, 1.155, et al. (gignō)

haereō, haesī, haesus, 2, n.: to stick; foll. by dat., or by abl. w. or without a prep.; hang, cling, adhere, cling to, 1.476, et al.; stop, stand fixed, 6.559; halt, 11.699; adhere to as companion, 10.780; stick to in the chase, 12.754; persist, 2.654; dwell, 4.4; pause, hesitate, 3.597; be fixed or decreed, 4.614.

interdum: (adv.), sometimes.

gremium, iī, n.: the lap, the bosom, 1.685, et al.; ante gremium suum, in front of or before one's self, 11.744.

foveō, fōvī, fōtus, 2, a.: to keep warm; (fig.), foster, protect, cherish, 1.281; soothe, 12.420; caress, make love to, 1.718; rest, incline, 10.838; to toy away, enjoy, 4.193; cherish, hope, long, desire, 1.18.

īnscius, a, um: not knowing; unaware, unwitting, ignorant, 1.718; amazed, bewildered, 2.307; w. gen., ignorant of, 12.648.

Dīdō, ūs or ōnis, f.: Dido, daughter of Belus, king of Phoenicia, who fled from her brother Pygmalion to Africa, where she founded the city of Carthage, 1.299.

īnsīdō, sēdī, sessus, 3, n.: to sink, take a seat, or settle upon; (w. dat.), alight upon, 6.708; to be stationed or secreted in, 11.531; (w. acc.), settle upon, 10.59.

quantus, a, um: (interrogative adjective) how great; what, 1.719, et al.

memor, oris: adj. (rel. to mēns and meminī), mindful, remembering, 1.23; heedful, 480; thankful, grateful, 4.539; not forgetting; relentless, 1.4; with nōn or nec, unmindful, regardless, 12.534.

Acīdalius, a, um: pertaining to Venus; Acidalian, 1.720. (Acīdalia, an appellation of Venus, derived from the name of a fountain in Boeotia)

paulātim: (adv.), little by little; gradually, 1.720. (paulum)

aboleō, ēvī, itus, 2, a.: to cause to wane or waste; to destroy, 4.497; cleanse, efface, wipe out, 11.789; obliterate the memory of, 1.720.

Sӯchaeus, ī, m.: a Tyrian prince, the husband of Dido, 1.343, et al.

vīvus, a, um: adj. (vīvō), alive, living, 6.531; lifelike, 6.848; immortal, 12.235; of water, living, running, pure, 2.719; of rock, natural, unquarried, living, 1.167.

praevertō, vertī, versus, 3, a.: to turn before; to preoccupy, prepossess, 1.721; surpass, 7.807; pass. as dep. (only in pres.), praevertor, to surpass, outstrip, 1.317.

iamprīdem: (adv.), some time before or since; long ago, long since, 2.647, freq.

reses, idis: adj. (resideō), that remains seated; (fig.), inactive, slothful, quiet, 6.813; sluggish, torpid, dormant, 1.722.

dēsuēscō (in poetry trisyll.), suēvī, suētus, 3, a. and n.: to become unaccustomed; p., dēsuētus, a, um, unaccustomed, unused, 6.814; neglected, unfamiliar, unpracticed, 2.509; unused to love; dormant, 1.722.