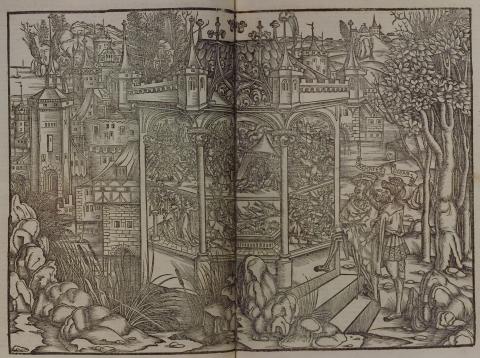

Aeneas and Achates, on the right, look at a mural on the walls of Juno's temple (446) at the edge of the city of Carthage. The mural contains vignettes from the Trojan war.

In the top left panel, Hector pursues some Greek soldiers, an interesting take on the first vignette. Vergil's description includes a depiction of the Greeks in temporary triumph over the Trojans (466-8); Brant puts this image in the second panel rather than the first. According to Servius, Hector is the Trojan youth, "TROIANAE IUVENTUS definitio est Hectoris," (1.467). Thus Brant made Hector the solitary stand-in for the Trojan army.

The top central panel has two images. The left side shows Automedon, Achilles' charioteer, on horseback, in the midst of soldiers, stabbing someone in the back with his sword. This is odd because neither the Iliad nor the Aeneid has him doing much of the combat fighting, and it does not make sense to show him on a horse. It would make more sense to show Achilles, rather than his charioteer. The right side shows Diomedes killing Rhesus (469-73), with Ulysses leading the horses of Rhesus to the Greek camp. Ulysses (Odysseus) is not included in Vergil's description, though he led the attack on the camp of Rhesus with Diomedes. Here, Brant lets his knowledge of the Iliad and other external sources influence his illustration; the attack on Rhesus takes place in Book 10 of the Iliad.

In the top right panel, Troilus, the youngest son of Priam, hangs upside down, holding onto his chariot with his knees and holding onto the reins in an attempt to regain control of his horse (475-8). Achilles in his own chariot stabs him in the neck with a sword, a reference to the full event which is commonly found in Archaic art (OCD). The crown of Troilus is shown under the horse of Achilles. With such a limited space, the arrangement of key elements is a bit awkward and forced, but Brant does manage to fit in most of the important details; he does not show Troilus's javelin dragging on the ground, which would be extremely difficult to show with the cramped arrangement.

In the lower left panel, the Trojan women supplicate a rather small statue of Pallas (479-482); they pray in a standard Christian manner rather than giving gifts and beating their breasts as described by Vergil (480-1). In the text, Pallas is unmoved by the appeals (483), but in the illustration there is no indication of her response.

In the lower middle panel, the left image, which is partially obscured in this photograph, shows Achilles dragging the body of Hector behind his horse, while Priam is labelled in the background (483-7). In the Iliad, this is a long poignant scene; Vergil devotes 5 lines to the full episode, with the first two lines devoted to Achilles dragging Hector and the last line describing Priam's humiliating attempt to gain back his son's body. On the right, Memnon [Mennon], the king of Ethiopia, lies dead on a funeral bed with birds above him, a reference to a story told in Book 13 of Ovid's Metamorphoses in which Zeus turns the smoke from Memnon's funeral pyre into smoke to appease Memnon's mother. Memnon is mentioned in line 489, but Vergil has him alive with masses of troops. The scene portrayed here comes from the Iliad, rather than the Aeneid.

In the lower right panel, Penthesilea [Patesilea], with mounted soldiers behind her, spears a soldier in the back, with troops looking on (490-3). It is difficult to tell the gender of any of the soldiers surrounding her, so it is hard to say whether her army is in fact all female, as it should be. (Katy Purington)

Woodcut illustration from the “Strasbourg Vergil,” edited by Sebastian Brant: Publii Virgilii Maronis Opera cum quinque vulgatis commentariis expolitissimisque figuris atque imaginibus nuper per Sebastianum Brant superadditis (Strasbourg: Johannis Grieninger, 1502), fol. 141v-142r, executed by an anonymous engraver under the direction of Brant.

Sebastian Brant (1458–1521) was a humanist scholar of many competencies. Trained in classics and law at the University of Basel, Brant later lectured in jurisprudence there and practiced law in his native city of Strasbourg. While his satirical poem Das Narrenschiff won him considerable standing as a writer, his role in the transmission of Virgil to the Renaissance was at least as important. In 1502 he and Strasbourg printer Johannes Grüninger produced a major edition of Virgil’s works, along with Donatus’ Life and the commentaries of Servius, Landino, and Calderini, with more than two hundred woodcut illustrations. (Annabel Patterson)