Hīs animum arrēctī dictīs et fortis Achātēs

et pater Aenēās iamdūdum ērumpere nūbem580

ārdēbant. Prior Aenēān compellat Achātēs:

'Nāte deā, quae nunc animō sententia surgit?

Omnia tūta vidēs, classem sociōsque receptōs.

Ūnus abest, mediō in flūctū quem vīdimus ipsī

submersum; dictīs respondent cētera mātris.'585

Vix ea fātus erat cum circumfūsa repente

scindit sē nūbēs et in aethera pūrgat apertum.

Restitit Aenēās clārāque in lūce refulsit

ōs umerōsque deō similis; namque ipsa decōram

caesariem nātō genetrīx lūmenque iuventae590

purpureum et laetōs oculīs adflārat honōrēs:

quāle manūs addunt eborī decus, aut ubi flāvō

argentum Pariusve lapis circumdatur aurō.

Tum sīc rēgīnam adloquitur cūnctīsque repente

imprōvīsus ait: 'Cōram, quem quaeritis, adsum,595

Trōïus Aenēās, Libycīs ēreptus ab undīs.

Ō sōla īnfandōs Trōiae miserāta labōrēs,

quae nōs, rēliquiās Danaüm, terraeque marisque

omnibus exhaustōs iam cāsibus, omnium egēnōs,

urbe, domō sociās, grātēs persolvere dignās600

nōn opis est nostrae, Dīdō, nec quidquid ubīque est

gentis Dardaniae, magnum quae sparsa per orbem.

Dī tibi, sī qua piōs respectant nūmina, sī quid

usquam iūstitiae est et mēns sibi cōnscia rēctī,

praemia digna ferant. Quae tē tam laeta tulērunt605

saecula? Quī tantī tālem genuēre parentēs?

In freta dum fluviī current, dum montibus umbrae

lūstrābunt convexa, polus dum sīdera pāscet,

semper honōs nōmenque tuum laudēsque manēbunt,

quae mē cumque vocant terrae.' Sīc fātus amīcum610

Īlionēa petit dextrā laevāque Serestum,

post aliōs, fortemque Gyān fortemque Cloanthum.

notes

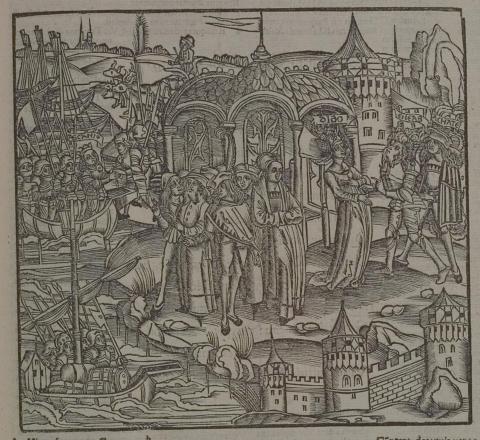

Achates and Aeneas long to make themselves known. Suddenly the mist disperses, and Venus makes her son as beautiful as a god. Aeneas reveals himself to Dido, saying that he will remember her always, everywhere (Austin).

The whole scene is a recollection of Odyssey VII 143 ff., where Ulysses suddenly appears. He addresses the queen and greets his comrades (Carter).

579 Animum arrēctī: “lifted up in spirit”; animum is accusative of respect after the passive participle (Austin).

580 Pater: the term marks Aeneas as a responsible leader; sometimes it implies an aspect of his pietas (Austin).

582: Nāte deā: “Goddess born” not “son of a goddess” (Comstock); vocative (AG 340); “you goddess-born” appropriate address, implying that Aeneas is under his mother's care (F-B). Here chosen to remind him of his mother’s recent prophecy (399) as 585 shows (Conway).

582 Surgit: represents a new thought as something living (so stare, sedere) and gives poetic color to the everyday word sententia (Conway).

583 Tūta: predicative, “that all is safe” (Conway).

584 Ūnus abest: i.e. Orontes, who was lost in the storm (F-D).

585 dictīs respondent cētera mātris: “all the rest agrees with (lit. 'answers to') your mother’s statement” (Comstock).

587 scindit sē … et pūrgat: se is the obj. of both scindit and purgat, “parts and clears itself away into the open sky” (Conway).

588 Restitit: “Stood revealed” (F-D) or “stood forth” (Carter).

589 deō: probably Apollo, whose head and shoulders are particularly praised (Carter).

590 caesariem: long flowing locks were an essential of manly beauty; and are characteristic of Apollo (Carter).

590 nātō genetrīx: a significant juxtaposition, “with a mother’s pride” (Conway).

590-91 lūmenque iuventae / purpureum: “the rosy light” i.e. “the rosy bloom of youth” (Chase). It is unfortunate that the word “purple,” always strange to English lips, has come to denote for us something bluish, instead of the glowing crimson, shot through with hues of mother of pearl (ostrum), which “Tyrian purple” meant to a Roman (Conway).

591 laetōs honōrēs: “sparkling beauty” from the joy of youth (F-D).

591 adflārat: syncopated form of adflaverat. “Had breathed” (Carter).

592 manūs: “skilled hands” or “the hands of artists” (Carter).

592 addunt: clearly of gilding, but equally clearly of gilt applied only to parts of the underlying material, as e.g. to the hair of a statue, which in that case might just as well be plaster as the costly materials here named (Conway).

593 Parius lapis: “marble of Paros,” of dazzling whiteness (Conway). Not just conventional: Parian marble had a luminous quality in its whiteness (Austin).

594 cūnctīs: dative, with improvisus (FD).

597 miserāta: a participle, equivalent to a relative clause, quae miserata es (FD).

598: quae nōs urbe, domō sociās: the verb is sociās (I. 600) (Carter), “You who grant us a share in your city (and your) palace.” domō and urbe are ablatives of association (Bennett). Ablatives of instrument (F-B).

599 omnium egēnōs: “destitute of all things” (Bennett).

600 persolvere: “to pay to the full,” observe the force of per (thoroughly) (Carter).

601 nōn opis est nostrae: "it is not in our power" (Carter), predicate genitive (AG 343b).

601 quidquid: eius gentis, or some other genitive, must be supplied to parallel opis est nostrae. “Nor is it in the power of this race, whatsoever of the Trojan race exists,” etc. (Carter).

603 sī quid ... iūstitia est: “if justice amounts to anything” (Carter).

603 dī tibi … ferant: “may the gods grant you” (Comstock). The gods are invoked to show great gratitude (Bennett).

606 tantī tālem: notice the emphatic juxtaposition (Carter).

607 montibus: either dative of reference (AG 377) or ablative of place where (AG 429.4) (Comstock).

montibus lūstrābunt convexa: “shall flit over the hollows on the hills” (Bennett).

608 pāscet: the stars are thought of as grazing like sheep in the sky, nourishing themselves on the little particles of fire contained in the aether (Carter). They were believed to be nourished by vapors arising from the Earth and the sea (Chase).

610 quae … cumque: tmesis, quaecumque = quācumque, “wherever” (Comstock).

611 Serestum: not to be confused with Sergestus, whose name we would naturally expect because he is mentioned (1. 510) among those whom Aeneas saw in the band of suppliants (Carter).

612 post: adverb.