οἱ δ᾽ ἄμυδις πυρσοῖο σέλας προπάροιθεν ἰδόντες,

τό σφιν παρθενικὴ τέκμαρ μετιοῦσιν ἄειρεν,

Κολχίδος ἀγχόθι νηὸς ἑὴν παρὰ νῆ᾽ ἐβάλοντο

ἥρωες: Κόλχον δ᾽ ὄλεκον στόλον, ἠύτε κίρκοι485

φῦλα πελειάων, ἠὲ μέγα πῶυ λέοντες

ἀγρότεροι κλονέουσιν ἐνὶ σταθμοῖσι θορόντες.

οὐδ᾽ ἄρα τις κείνων θάνατον φύγε, πάντα δ᾽ ὅμιλον

πῦρ ἅ τε δηιόωντες ἐπέδραμον: ὀψὲ δ᾽ Ἰήσων

ἤντησεν, μεμαὼς ἐπαμυνέμεν οὐ μάλ᾽ ἀρωγῆς490

δευομένοις: ἤδη δὲ καὶ ἀμφ᾽ αὐτοῖο μέλοντο.

ἔνθα δὲ ναυτιλίης πυκινὴν περὶ μητιάασκον

ἑζόμενοι βουλήν: ἐπὶ δέ σφισιν ἤλυθε κούρη

φραζομένοις: Πηλεὺς δὲ παροίτατος ἔκφατο μῦθον:

ἤδη νῦν κέλομαι νύκτωρ ἔτι νῆ᾽ ἐπιβάντας495

εἰρεσίῃ περάαν πλόον ἀντίον, ᾧ ἐπέχουσιν

δήιοι: ἠῶθεν γὰρ ἐπαθρήσαντας ἕκαστα

ἔλπομαι οὐχ ἕνα μῦθον, ὅτις προτέρωσε δίεσθαι

ἡμέας ὀτρυνέει, τοὺς πεισέμεν: οἷα δ᾽ ἄνακτος

εὔνιδες, ἀργαλέῃσι διχοστασίῃς κεδόωνται.500

ῥηιδίη δέ κεν ἄμμι, κεδασθέντων δίχα λαῶν,

ἤ τ᾽ εἴη μετέπειτα κατερχομένοισι κέλευθος.

ὧς ἔφατ᾽: ᾔνησαν δὲ νέοι ἔπος Λἰακίδαο.

ῥίμφα δὲ νῆ᾽ ἐπιβάντες ἐπερρώοντ᾽ ἐλάτῃσιν

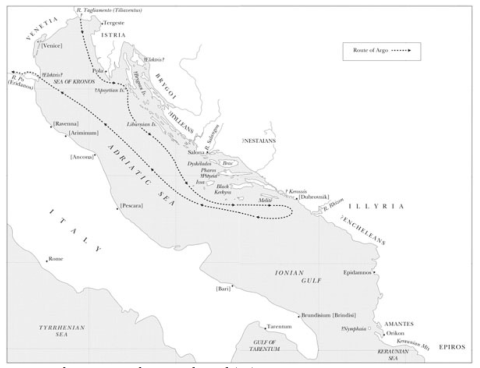

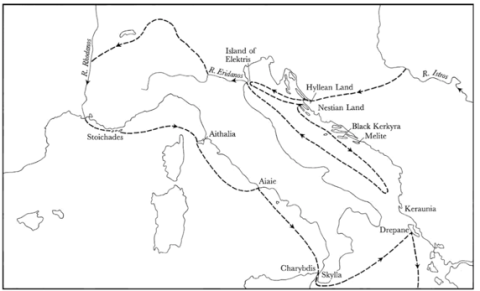

νωλεμές, ὄφρ᾽ ἱερὴν Ἠλεκτρίδα νῆσον ἵκοντο,505

ἀλλάων ὑπάτην, ποταμοῦ σχεδὸν Ἠριδανοῖο.

Κόλχοι δ᾽ ὁππότ᾽ ὄλεθρον ἐπεφράσθησαν ἄνακτος,

ἤτοι μὲν δίζεσθαι ἐπέχραον ἔνδοθι πάσης

Ἀργὼ καὶ Μινύας Κρονίης ἁλός. ἀλλ᾽ ἀπέρυκεν

Ἥρη σμερδαλέῃσι κατ᾽ αἰθέρος ἀστεροπῇσιν.510

ὕστατον αὖ (δὴ γάρ τε Κυταιίδος ἤθεα γαίης

στύξαν, ἀτυζόμενοι χόλον ἄγριον Αἰήταο),

ἔμπεδα δ᾽ ἄλλυδις ἄλλοι ἐφορμηθέντες ἔνασθεν.

οἱ μὲν ἐπ᾽ αὐτάων νήσων ἔβαν, ᾗσιν ἐπέσχον

ἥρωες, ναίουσι δ᾽ ἐπώνυμοι Ἀψύρτοιο:515

οἱ δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἐπ᾽ Ἰλλυρικοῖο μελαμβαθέος ποταμοῖο,

τύμβος ἵν᾽ Ἁρμονίης Κάδμοιό τε, πύργον ἔδειμαν,

ἀνδράσιν Ἐγχελέεσσιν ἐφέστιοι: οἱ δ᾽ ἐν ὄρεσσιν

ἐνναίουσιν, ἅπερ τε Κεραύνια κικλήσκονται,

ἐκ τόθεν, ἐξότε τούσγε Διὸς Κρονίδαο κεραυνοὶ520

νῆσον ἐς ἀντιπέραιαν ἀπέτραπον ὁρμηθῆναι.

ἥρωες δ᾽, ὅτε δή σφιν ἐείσατο νόστος ἀπήμων,

δή ῥα τότε προμολόντες ἐπὶ χθονὶ πείσματ᾽ ἔδησαν

Ὑλλήων. νῆσοι γὰρ ἐπιπρούχοντο θαμειαὶ

ἀργαλέην πλώουσιν ὁδὸν μεσσηγὺς ἔχουσαι525

οὐδέ σφιν, ὡς καὶ πρίν, ἀνάρσια μητιάασκον

Ὑλλῆες: πρὸς δ᾽ αὐτοὶ ἐμηχανόωντο κέλευθον,

μισθὸν ἀειρόμενοι τρίποδα μέγαν Ἀπόλλωνος.

δοιοὺς γὰρ τρίποδας τηλοῦ πόρε Φοῖβος ἄγεσθαι

Αἰσονίδῃ περόωντι κατὰ χρέος, ὁππότε Πυθὼ530

ἱρὴν πευσόμενος μετεκίαθε τῆσδ᾽ ὑπὲρ αὐτῆς

ναυτιλίης: πέπρωτο δ᾽, ὅπῃ χθονὸς ἱδρυνθεῖεν,

μήποτε τὴν δῄοισιν ἀναστήσεσθαι ἰοῦσιν.

τούνεκεν εἰσέτι νῦν κείνῃ ὅδε κεύθεται αἴῃ

ἀμφὶ πόλιν ἀγανὴν Ὑλληίδα, πολλὸν ἔνερθεν535

οὔδεος, ὥς κεν ἄφαντος ἀεὶ μερόπεσσι πέλοιτο.

οὐ μὲν ἔτι ζώοντα καταυτόθι τέτμον ἄνακτα

Ὕλλον, ὃν εὐειδὴς Μελίτη τέκεν Ἡρακλῆι

δήμῳ Φαιήκων. ὁ γὰρ οἰκία Ναυσιθόοιο

Μάκριν τ᾽ εἰσαφίκανε, Διωνύσοιο τιθήνην,540

νιψόμενος παίδων ὀλοὸν φόνον: ἔνθ᾽ ὅγε κούρην

Αἰγαίου ἐδάμασσεν ἐρασσάμενος ποταμοῖο,

νηιάδα Μελίτην: ἡ δὲ σθεναρὸν τέκεν Ὕλλον.

οὐδ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ὅγ᾽ ἡβήσας αὐτῇ ἐνὶ ἔλδετο νήσῳ

ναίειν, κοιρανέοντος ὑπ᾽ ὀφρύσι Ναυσιθόοιο:

βῆ δ᾽ ἅλαδε Κρονίην, αὐτόχθονα λαὸν ἀγείρας

Φαιήκων: σὺν γάρ οἱ ἄναξ πόρσυνε κέλευθον

ἥρως Ναυσίθοος: τόθι δ᾽ εἵσατο, καί μιν ἔπεφνον550

Μέντορες, ἀγραύλοισιν ἀλεξόμενον περὶ βουσίν.

notes

vocabulary

ἄμυδις, together, at the same time

πυρσός, a firebrand, torch

σέλας τό, a bright flame, blaze, light

προπάροιθε, before, in front of

τέκμαρ, a fixed mark

ἀγχόθι, near

Κόλχος ὁ, a Colchian 485

ὀλέκω, to ruin, destroy, kill

στόλος -ου ὁ, expedition

ἠύτε, as, like as

κίρκος ὁ, hawk

φῦλον τό, flock, tribe

πελειάς ἡ, dove

πῶυ τό, a flock

ἀγρότερος, wild

κλονέω, to drive in confusion, drive before one

σταθμός ὁ, a fold

θρῴσκω, to leap, spring

θάνατος -ου ὁ, death

φεύγω φεύξομαι ἔφυγον πέφευγα --- ---, flee

ὅμιλος -ου ὁ, group, crowd

δηιόω, to cut down, slay

ἐπιτρέχω, to run upon, attack

ὀψέ, late

ἀντάω, to encounter, meet with, join 490

μάω, be eager, press on

ἐπαμύνω, to come to aid, defend, assist

ἀρωγή, help, aid, succour, protection

δεύω to miss, want

μέλω, μέλομαι, be an object of care or interest

ναυτιλίη ἡ, voyage

πυκινός, wise

μητιάω, to meditate, deliberate, debate

ἕζομαι, sit down

φράζω φράσω ἔφρασα πέφρακα πέφρασμαι ἐφράσθην, advise, design

Πηλεύς ὁ, Peleus (Νame)

παροίτατος, first of all

ἔκφημι, to speak out

κέλομαι, command, urge on, exhort, call to 495

νύκτωρ, by night

εἰρεσίη ἡ, rowing

περάω περάσω (or περῶ) ἐπέρασα πεπέρακα --- ---, to cross, row

πλόος ὁ, a sailing, voyage

ἀντίον, opposite, over against

ἐπέχω, control

δήιος, hostile, pl. the enemy

ἠῶθεν, at dawn, in the morning

ἐπαθρέω, discover

προτέρωσε, toward the front, forward

δίεμαι, to pursue

ὀτρύνω, urge on, encourage

πείθω πείσω ἔπεισα πέπεικα (or πέποιθα) πέπεισμαι ἐπείσθην, persuade

ἄναξ -ακτος ὁ, ruler, lord

εὖνις, deprived of 500

ἀργαλέος -α, -ον, hard to endure or deal with, difficult

διχοστασίη ἡ, dissension

κεδάννυμι, to break asunder, break up, scatter

ῥηΐδιος, η, ον, easy

δίχα, apart

λαός -οῦ ὁ, people, host

κατέρχομαι, to go down from, return

κέλευθος ὁ, a road, way, path, track

αἰνέω αἰνέσω ᾔνεσα ᾔνεκα ᾔνημαι ᾔνέθην, praise

Αἰακίδης, son of Aeacus i.e. Peleus

ῥίμφα, lightly, swiftly, fleetly

ἐπιρρώομαι, to row, to work vigorously at something.

ἐλάτη, ἡ, an oar

νωλεμές, without pause, unceasingly, continually 505

Ἠλεκτρίς, of Electra, name of a group of islands in the Adriatic

νῆσος -ου ἡ, island

ὕπατος -η -ον, highest, the top of

σχεδόν, near, almost

Ἠριδανός, Eridanus (River)

ὁππότε, when

ὄλεθρος, ruin, destruction, death

ἐπιφράζω, to notice, observe

δίζημαι, to seek out, look for

ἐπιχράω, to rage, to be urgent or eager to do

Μινύαι, the Minyans

Κρόνιος, Saturnian, of Cronus

ἀπερύκω, to keep off

Ἥρη ἡ, Hera

σμερδαλέος, terrible, fearful 510

αἰθήρ ἡ, ether, the sky

ἀστεροπή ἡ, lightning

ὕστατος -η -ον, latest, last

Κυταιίς -ίδος, ἡ, Kytaian, Colchian (Name)

ἦθος -ους τό, home, haunt

στυγέω, hate

ἀτύζομαι, to be distraught from fear, bewildered

χόλος -ου ὁ, anger

ἄγριος -α -ον, savage; wild; fierce

ἔμπεδον, lasting, continual

ἄλλυδις, elsewhere

ἀφορμάω, to make start from, set off

ναίω, dwell, inhabit, be situated

ἐπέχω ἐφέξω ἐπέσχον ἐπέσχηκα --- ---, go on to, οψψθπυ.

ἐπώνυμος, given as a name 515

Ἰλλυρικός, ή, όν, Illyrian

μελαμβαθής, black and deep

τύμβος ὁ, a sepulchral mound, cairn, barrow

Ἁρμονί-ας, ἡ, Harmonia (Name)

Κάδμος, Cadmus (Name)

πύργος -ου ὁ, fortress, fortified town, tower

δέμω, to build

Ἐγχελεῖς -εῶν, οἱ, Enchelees (Name)

ἐφέστιος, dwelling with, at one's own fireside, at home

ἐνναίω, to dwell in

Κεραύνιος, of a thunderbolt, Ceraunian

κικλήσκω, to call, summon

τόθεν, hence, thence 520

ἐξότε, from the time when

Κρονίδης ὁ, son of Cronus

κεραυνός ὁ, a thunderbolt

ἀντιπέραιος, α, ον, lying over against

ἀποτρέπω, to turn

ὁρμάω ὁρμήσω ὥρμησα ὥρμηκα ὥρμημαι ὡρμήθην, start, travel to

εἴδομαι, are visible, appear

ἀπήμων, safe, without harm

προβλώσκω, to go onwards

πεῖσμα τό, a ship's cable

δέω δήσω ἔδησα δέδεκα δέδεμαι ἐδέθην, bind, fetter

Ὑλλήες - οἱ, Hylloi/Hyllees (name)

ἐπιπροέχομαι, stand forward, project

θαμέες, crowded, close-set, thick

ἀργᾰλέος -α, -ον, difficult 525

πλέω πλεύσομαι ἔπλευσα πέπλευκα --- ---, sail, go by sea

μεσσηγὺς, in the middle, between

ἀνάρσιος, hostile, inplacable

μητιάω, to plan

μηχανάομαι, contrive, plan

κέλευθος ὁ, a road, way, path, track

μισθός -οῦ ὁ, wages, pay, hire

ἀείρω, to lift, heave, raise up

τρίπους ὁ, tripod

Ἀπόλλων ὁ, Apollo

δοιοί, two, both

τηλοῦ, afar, far off

πόρω, pres. not attested; aor. to furnish, offer, present

Φοῖβος ὁ, Phoebus

περάω περάσω (or περῶ) ἐπέρασα πεπέρακα --- ---, to pass through, journey 530

χρέος, an obligation, debt, mission

ὁππότε, when

Πυθώ ἡ, Pytho, the region of Delphi

μετακιάθω, to follow after

ὅπῃ, wherever

χθών χθονός ἡ, the earth, ground

ἱδρύω ἱδρύσω ἵδυρσα ἵδρυκα ἵδρυμαι ἱδρύθην, make sit down, seat

ἀνίστημι ἀνστήσω ἀνέστησα (or ἀνέστην), to be made to emigrate

τοὔνεκα, for that reason, therefore

εἰσέτι, still yet

κεύθω, to cover quite up, to cover, hide

ἀγανός, mild, gentle, kindly (see notes) 535

Ὑλληίς -ίδος, ἡ, Hylle (name)

ἔνερθε, beneath

οὖδας, the surface of the earth, the ground, earth

ἄφαντος, invisible, hidden

μέροψ, mortal (men)

καταυτόθι, in that place

τέτμον, find, come upon (Ep. aor. without any pres. in use)

Ὕλλος ὁ, Hyllus (name: see notes)

εὐειδής, beautiful, fair

Μελίτη ἡ, Melite

τίκτω τέξομαι ἔτεκον τέτοκα --- ---, beget, bear

Ἡρακλέης ὁ, Heracles

δῆμος -ου ὁ, common people, district

Φαίηξ, ηκος, ὁ, Phaeacian

οἰκίον τό, house, palace (always plural)

Ναυσίθοος ὁ, Nausithous

Μάκρις, ἡ, Makris (name) 540

Διώνυσος ὁ, Ep. for Διονυσος

τιθήνη ἡ, a nurse

νίζω, to wash the hands, cleanse from murder.

ὀλοός, destructive, fatal, deadly

φόνος -ου ὁ, murder, slaughter, corpse

Αἰγαῖος, Aegaeos (a river)

δαμάζω, to force, seduce

ἐράω, love, be in love with

Ναϊάς ἡ, Naiad, river-nymph, spring-nymph

Μελίτη ἡ, Melite (Νame)

σθεναρός, strong, mighty

τίκτω τέξομαι ἔτεκον τέτοκα --- ---, beget, bear

ἡβάω, to grow up

ἔλδομαι, to wish, long

κοιρανέω, to be lord 545

ὀφρύς ἡ, the brow, eyebrow

ὑπ᾿ ὀφρύσι, under the haughty gaze of

Ναυσίθοος, Nausithous (Νame)

Κρόνιος, Saturnian, of Cronus

αὐτόχθων, sprung from the land itself

λαός -οῦ ὁ, people, host

ἀγείρω ἤγειρα ἀγήγερμαι ἠγέρθην, gather, collect

πορσύνω, to offer, present

Ναυσίθοος ὁ, Nausithous 550

τόθι, there, in that place

ἵζω, to settle

θείνω, to strike, wound

Μέντορες, Mentores (an Illyrian tribe)

ἄγραυλος, dwelling in the field

ἀλέξω, to defend